Effectively Implementing the Science of Reading: Combining Science and Art

Over the last few weeks, we've shared some ideas (like reading is NOT rocket science and we shouldn't always rely just on what the research says) and you all had a LOT to say about them.

Some of you agreed with us, others were curious about learning more, and a few of you told us we were downright wrong.

If you want to read more about these ideas, we've linked the blog posts above. Today, we're going to elaborate on these beliefs and explain what they look like in practice.

First things first, when we look at the practice of teaching reading, there are two steps that we follow.

Step 1: Lay the foundation using the comprehensive body of research (known as the Science of Reading).

Step 2: Use your data + experience as an educator to navigate through and expand upon this foundation.

Let's dive into both.

Step 1: Lay the foundation using research

When we think about reading, a lot of research has been done that helps us understand the reading brain and the core components of literacy. You can read a full blog all about that >>here.<<

To simplify it, in our brain, there are three neural processors that need to activate and connect to support reading. These are the orthography (visual), phonology (sound), and semantics (meaning) processors. To support each of these (and the connections between them), we want to make sure that our lessons target phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, reading fluency, comprehension, and writing.

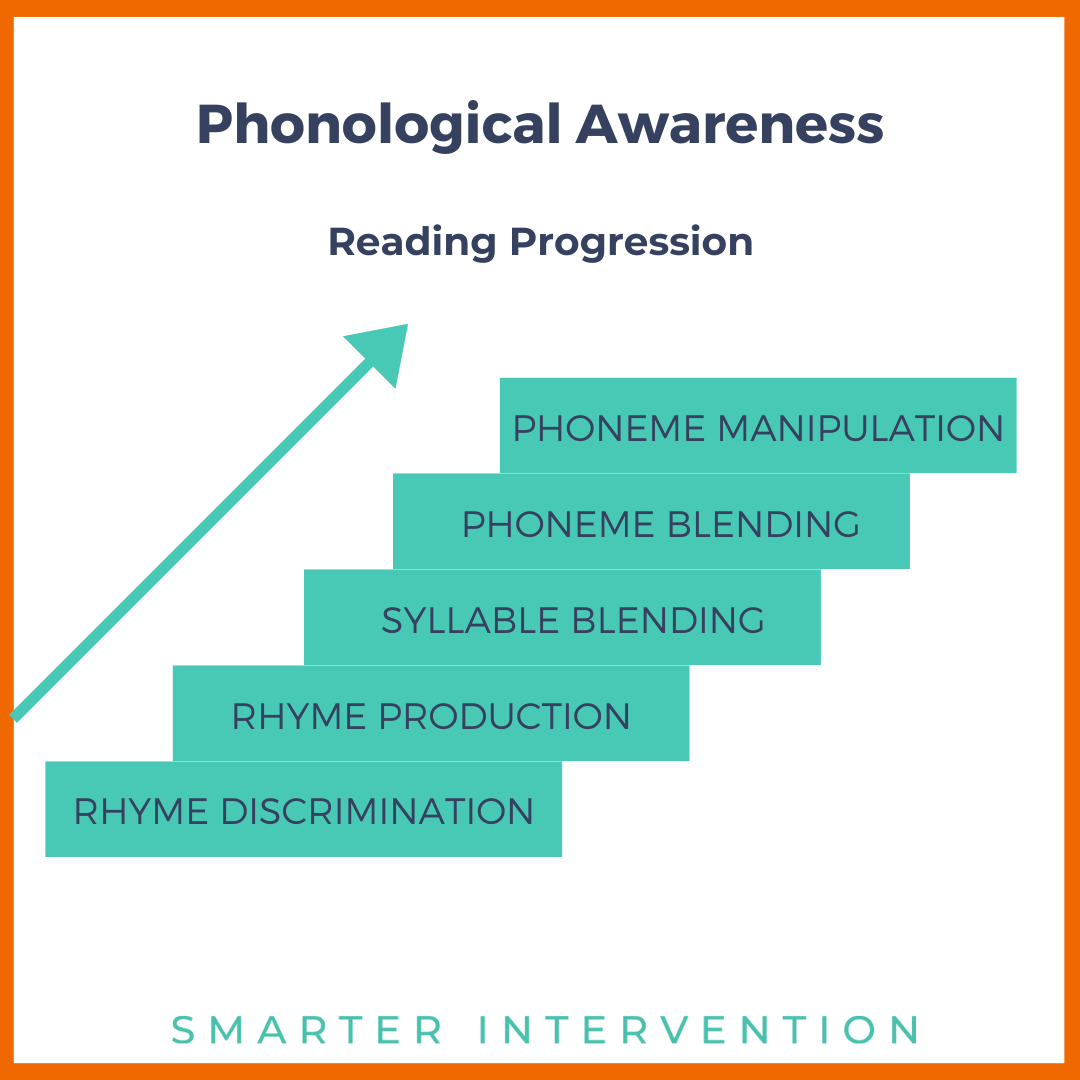

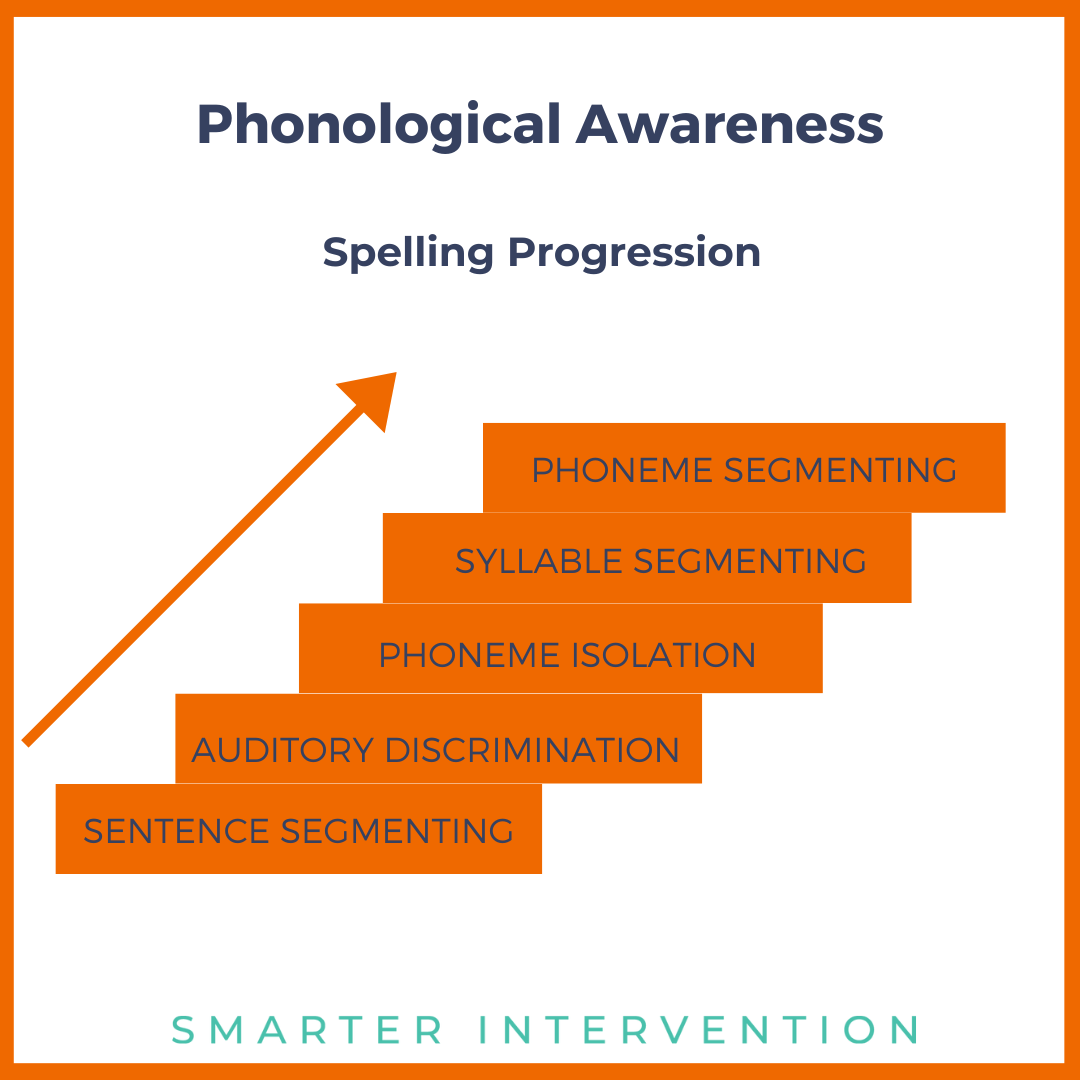

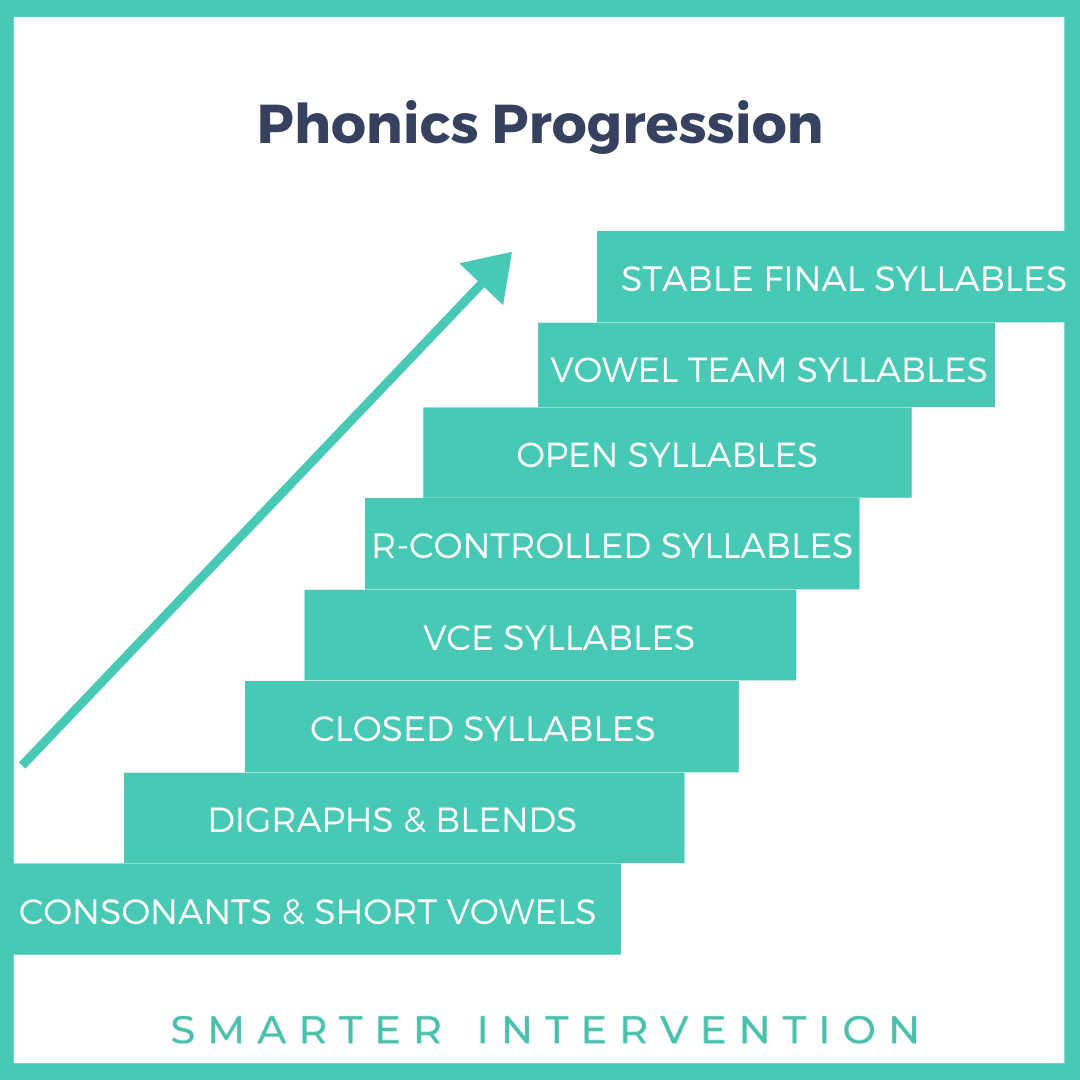

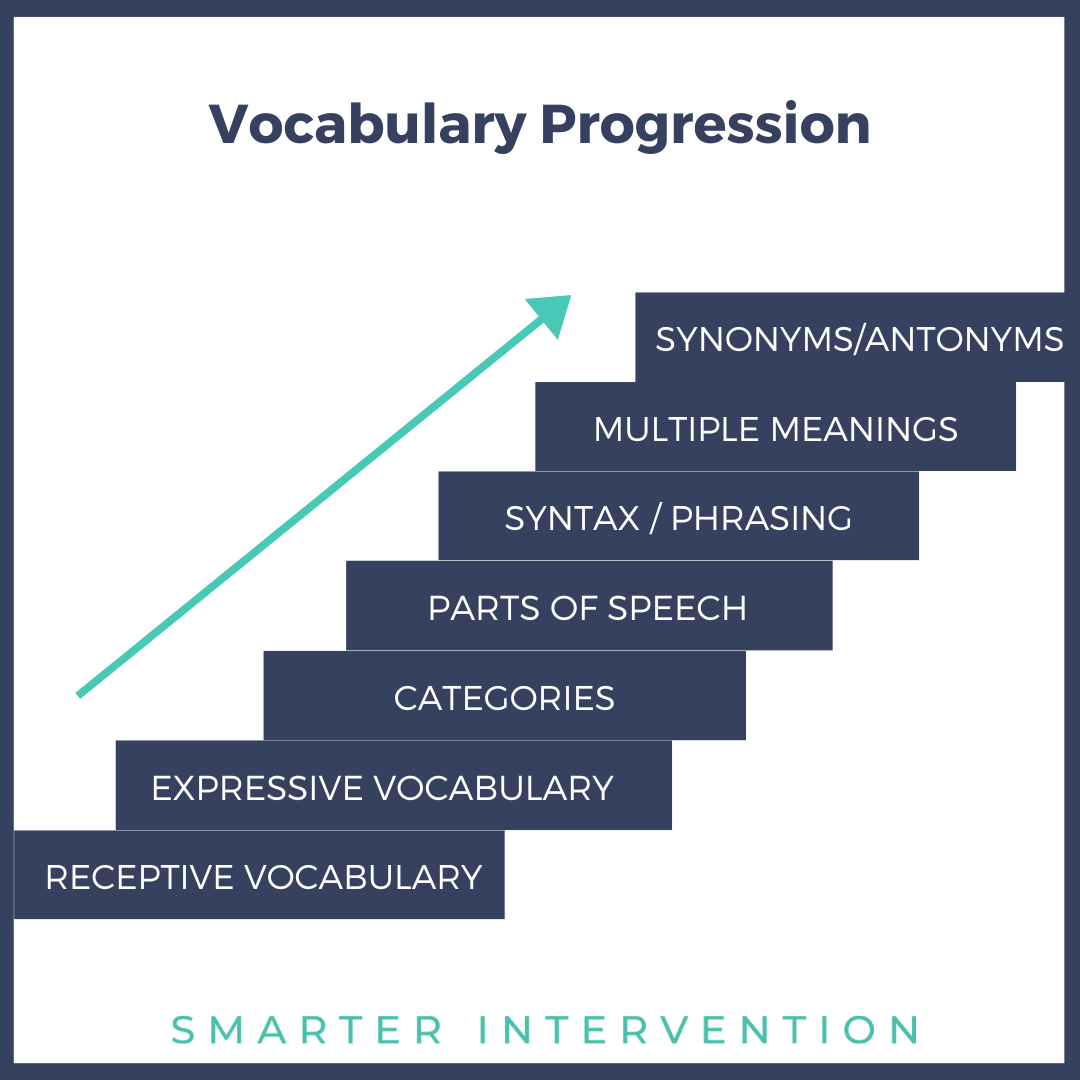

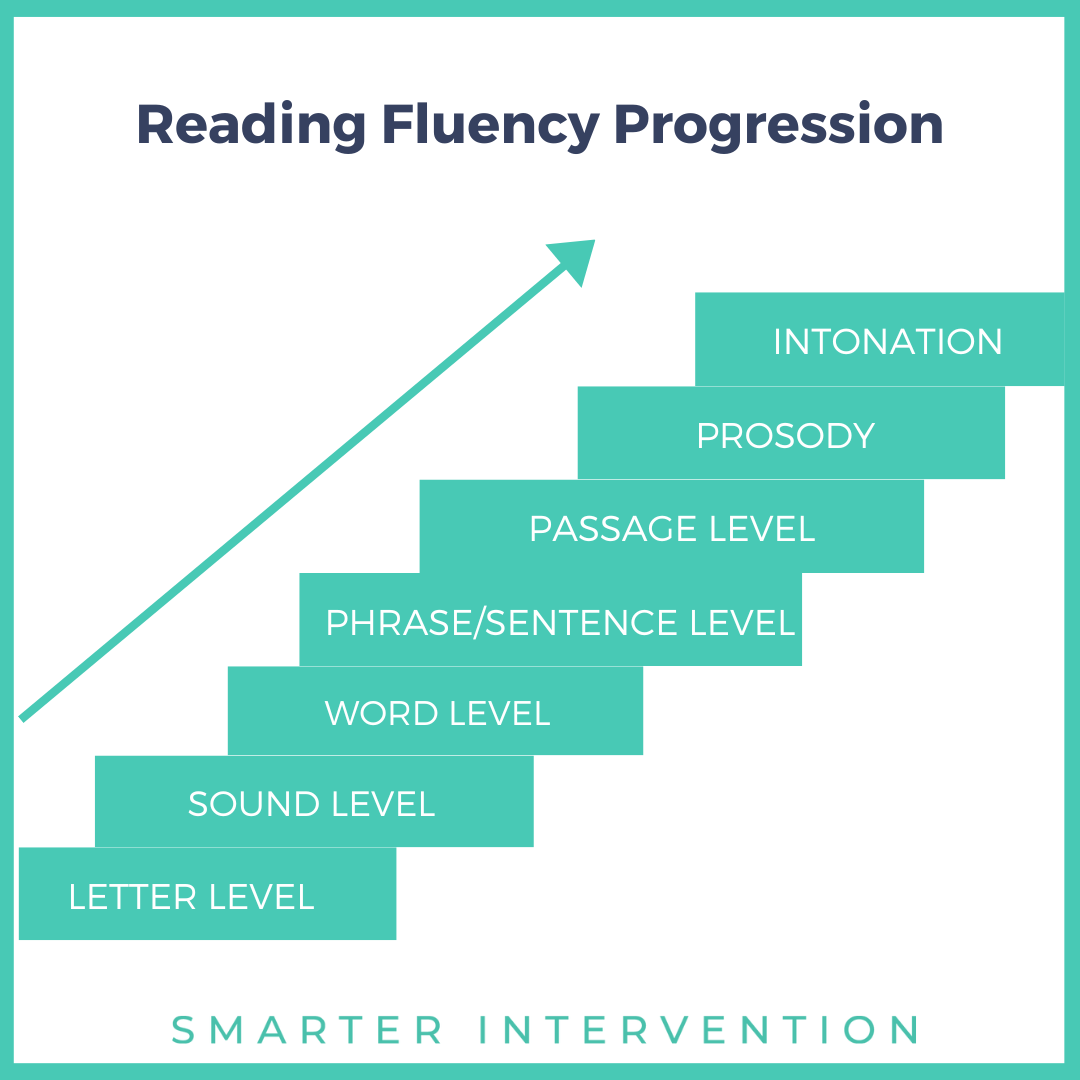

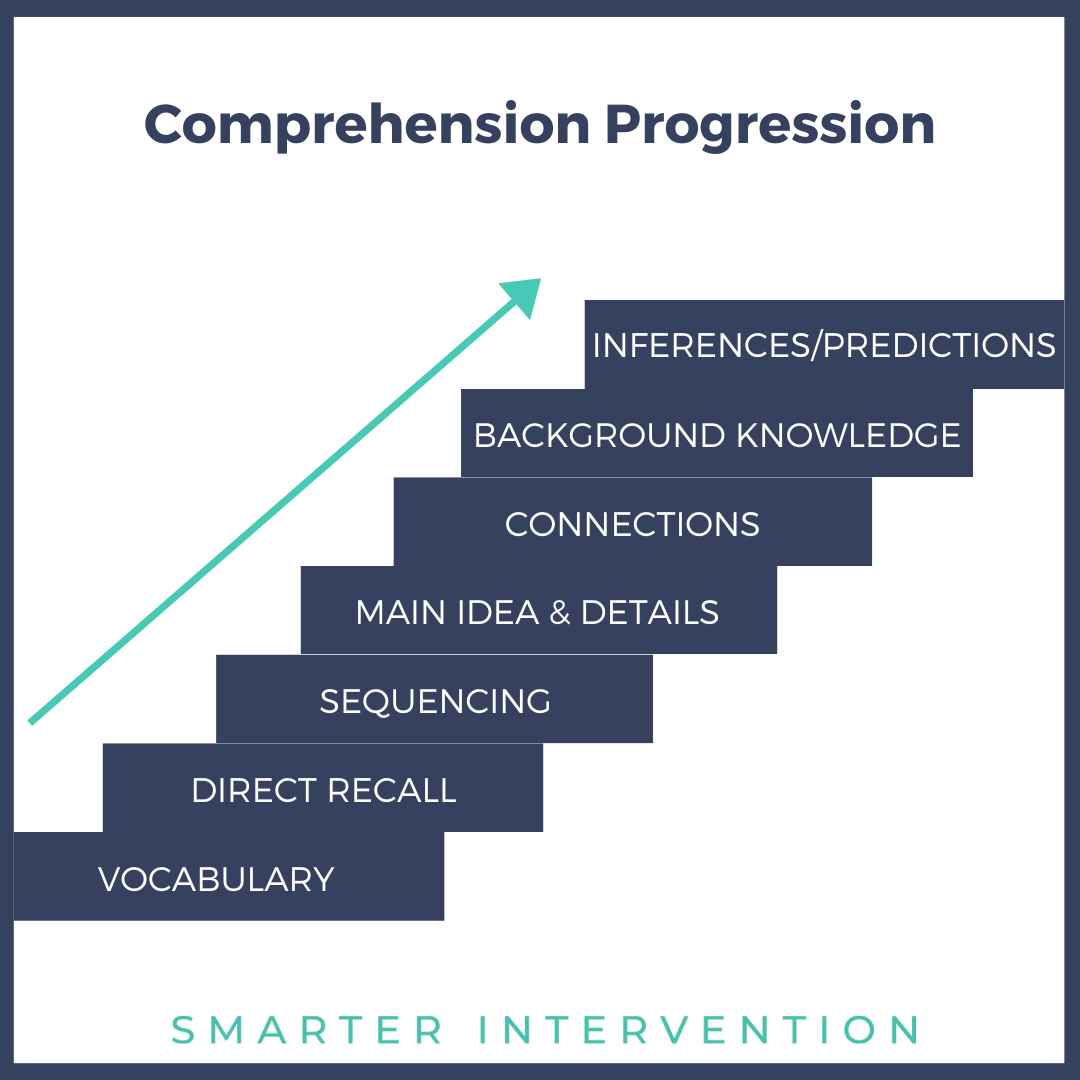

Within each of these skills, there are also subskills that we want to target to be sure that we are supporting the full scope of these skills. This means that in each lesson, we will include activities that target phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, reading fluency, comprehension, and writing and that over time, the instruction for each of these core components hits on each step of the skill progressions seen below.

If you are new to the Science of Reading (or feeling overwhelmed - we've ALL been there, trust us!) then working solely at this first level will ensure that you are targeting everything you need to provide effective literacy instruction.

If you want to increase efficiency and optimize this instruction, then once you have a solid lesson framework you're ready to move on to…

Step 2: The Art of Teaching Reading

Use your data + your experience with students to customize the lessons you built in step 1

We often say that the Science of Reading is as much an art as it is a science. That's because the most successful educators know that their instruction (within the scope of the research-based framework from step 1) can and should be flexible. They adapt to meet the needs of each student, group, or class. They recognize what has been working and not working in their instruction and allow themselves to build upon that as new research comes out and students’ needs evolve.

In order to optimize our Science of Reading-based instruction, we need to consider the following…

Where are students struggling? Do they need to go through every core component of literacy in every lesson?

While step 1 is going to tell us to teach PA, phonics, vocab, fluency, comprehension, and writing in each lesson, it is okay to deviate from this plan if our data tells us that students aren't struggling in a certain area.

For example, if a student is consistently scoring highly for PA and phonics, but low on vocab, fluency, and comprehension, we will spend much more time on the latter skills and much less time where students are already succeeding.

While we don't tend to get rid of any core component of literacy completely (we'll always pull in review here and there to help retention and to make sure to explicitly show students how that skill fits into the bigger picture), if a student is solid in a certain area, we won't waste time targeting it with multiple trials week, over week, over week. Again - we let the data guide this!

How quickly/slowly to progress through reading lessons

Probably the most frequent question we get asked is how long we spend on each skill with each child.

The easy answer is - it depends!

The longer answer is - it depends on a lot of factors. How long do we have with these students (i.e., are we seeing them for eight weeks? a year? indefinitely?), How is their skill retention week to week? Are they struggling with all core components of literacy or just this skill? Is there room to move on and build in more review? Do they have a support system at home that is helping with home-practice activities? Are we seeing this student one-on-one or in a group? What speed overwhelms them? What speed keeps them engaged? Are they struggling to attend because they're bored? Etc.

While we could provide an easy answer and pacing recommendations, the truth is only YOU know the pacing that is going to work best for your student(s) and setting. This is where your experience is invaluable - you know what speed is going to bore the student and what is going to overwhelm them. YOU get to experience the trial-and-error of pacing activities in different ways that we/other curriculum developers (since we don't work with your specific students) will never get to.

How to make reading lessons engaging for your students

Listen - educators know better than ANYONE that if students are bored or don't want to be there, they aren't going to learn something as well as students who are engaged.

This makes sense! Think about the last PD workshop you attended. Did YOU choose to go or did your school/company mandate that you be there? Did you find value in it? Were you engaged or were you doing boring/difficult work the entire time while you felt like you had better things to do?

We need to make this work engaging for students if we want them to truly get the most out of our lessons. For some, this means games. Where can you swap a word list with a reading game? Where you can gamify your instruction? For others, this means working towards a reward or a break. For some, it means reading about tennis instead of camping or vice versa.

Again - your experience with your students is going to clue you into how to best keep them engaged. What strategies have worked best in your classroom to keep students (as a whole) on task? Can students pick one of three passage choices to help their perceived buy-in? Can you swap a keyword/image with one that your students like?

I have a student who loves science and absolutely HATES spelling. When explaining the steps to spelling (i.e., Do we know the word? How many syllables do we hear/what sounds do we hear? What letters make those sounds? Are there any rules we need to remember?), we call it the "spellingtific method" because it sounds like "scientific method" and he feels like he relates to that better. I tried that same strategy with one of my other students and she laughed because she thought it was dumb. Not everything is going to work for each kid and that's okay!

So, when it comes to effectively implementing the Science of Reading - we need BOTH science and art.

We need a research-based foundation that supports the necessary literacy components AND we need to feel comfortable using OUR data and experiences with students to deviate from the script when necessary.

Stay tuned because over the next several weeks, we are going to break down exactly what this looks like in practice. We're going to take each section of our lessons and explain why we complete it, how it looks in practice, and where/when we pull in our own data/experiences to deviate from the script a bit to better serve our kids.

In the meantime, be sure to download our Science of Reading Blueprint for more information.