How to Teach Sight Words using a Research-Based Approach

In reading intervention we hear terms like sight words, high-frequency words, phonetically irregular words, red words, heart words, and so many other variations used every day. So we are jumping in to explain what these words actually are, and what the research says about how we should be teaching them!

First things first -

What are sight words?

Sight words are words that need to be recognized by “sight” or words that we need to automatically recognize without sounding the word out. Basically, they are words we can read automatically without thinking about them.

Why are sight words important?

Sight words are important because students need to have a certain level of automaticity to comprehend what they are reading. The tricky thing is that students need to be taught a systematic set of rules and patterns to decode words effectively. When students are learning to read, they should be working through a progression of concepts as they’re learning to “sound out” words. We talked more about this progression over here!

However, there are many words that students need to know before they get to that level of progression because they come up so frequently. This is why sight words are also known as high-frequency words. Because they come up so often, it can be helpful to teach students these patterns a little earlier in their instructional journey.

Now that said, we don’t need to have students memorize these words. Instead, we can use a systematic framework and progression to help build a foundation for future learning while also giving students the knowledge they need to be successful at their current level.

There are 7 Steps to a SMARTER Research-Based Instruction Framework (we use the acronym SMARTER to help remember each of the key components!)

1 - Systematic Instruction

Sight words (words that need to be learned by sight) can be taught systematically

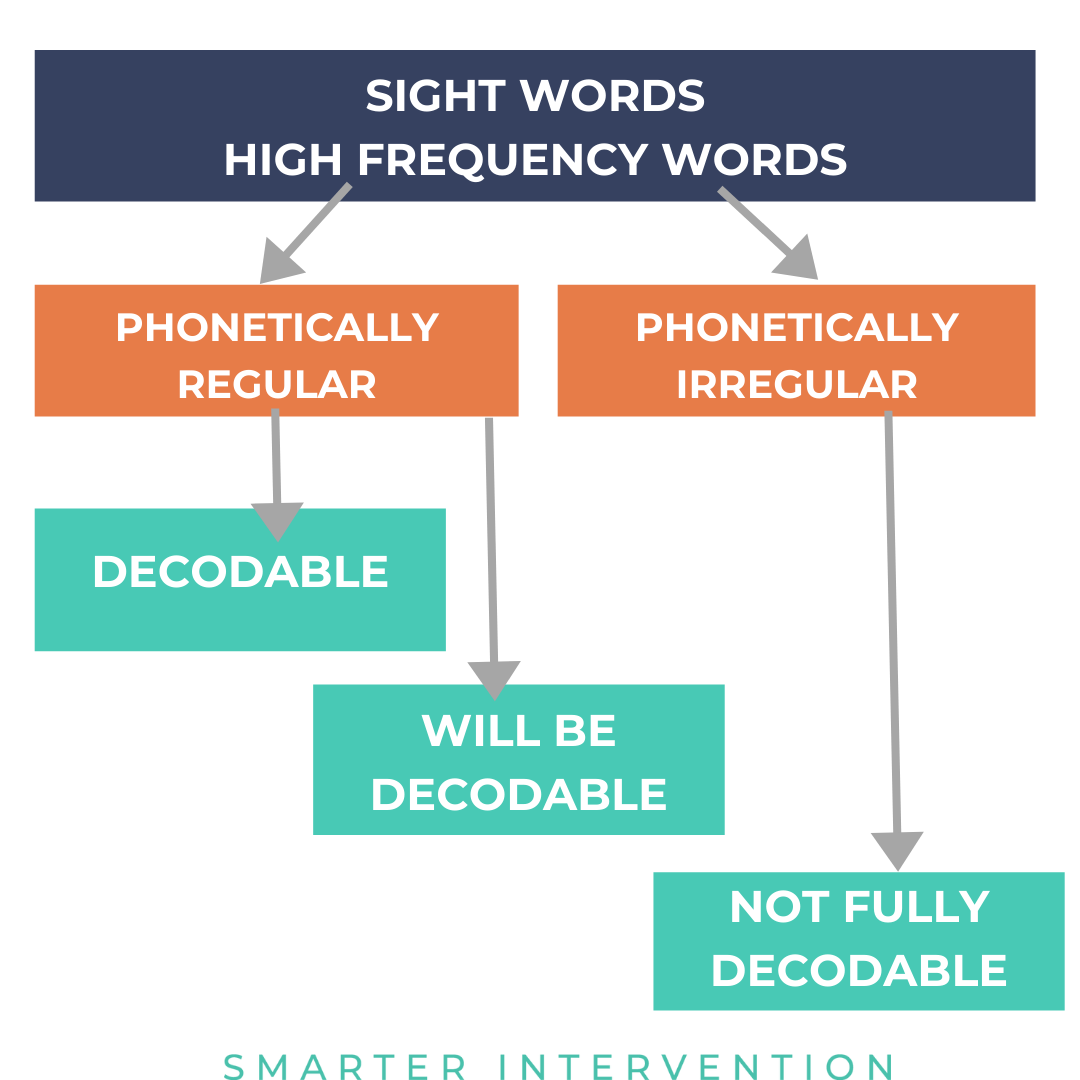

When we are thinking about teaching words that need to become sight words, we want to focus on high-frequency words (words that occur frequently). We can divide those high-frequency words into two categories.

1 - Are they phonetically regular? (Can they be sounded out?)

or

2 - Are they phonetically irregular? (Is there one or more sound patterns that cannot be sounded out even after students have progressed through a systematic phonics progression?)

Once we have sorted our sight words or high-frequency words into those two groups, we have one more question to consider.

3 - If the word is phonetically regular (able to be sounded out effectively), does the student have all the foundational knowledge of each letter pattern in order to read it? For example, the word “them” is phonetically regular and can be sounded out effectively as /th/ /e/ /m/, however, if a student hasn’t learned that TH says /th/ it is a pattern that will be decodable but is not yet.

What does decodable mean?

A decodable word is a word that can be sounded out with a student’s current level of knowledge. So for example, if a student has learned that U says /u/ and S says /s/ the word “us” is decodable. In the example provided above, the word “them” will be decodable as soon as a student learns that TH says /th/.

Or, if we consider the word “bird” bird is decodable if students know that “IR” says /r/.

In this case, students would need to be familiar with the R-controlled syllable type but as soon as they are familiar with that pattern the word becomes decodable.

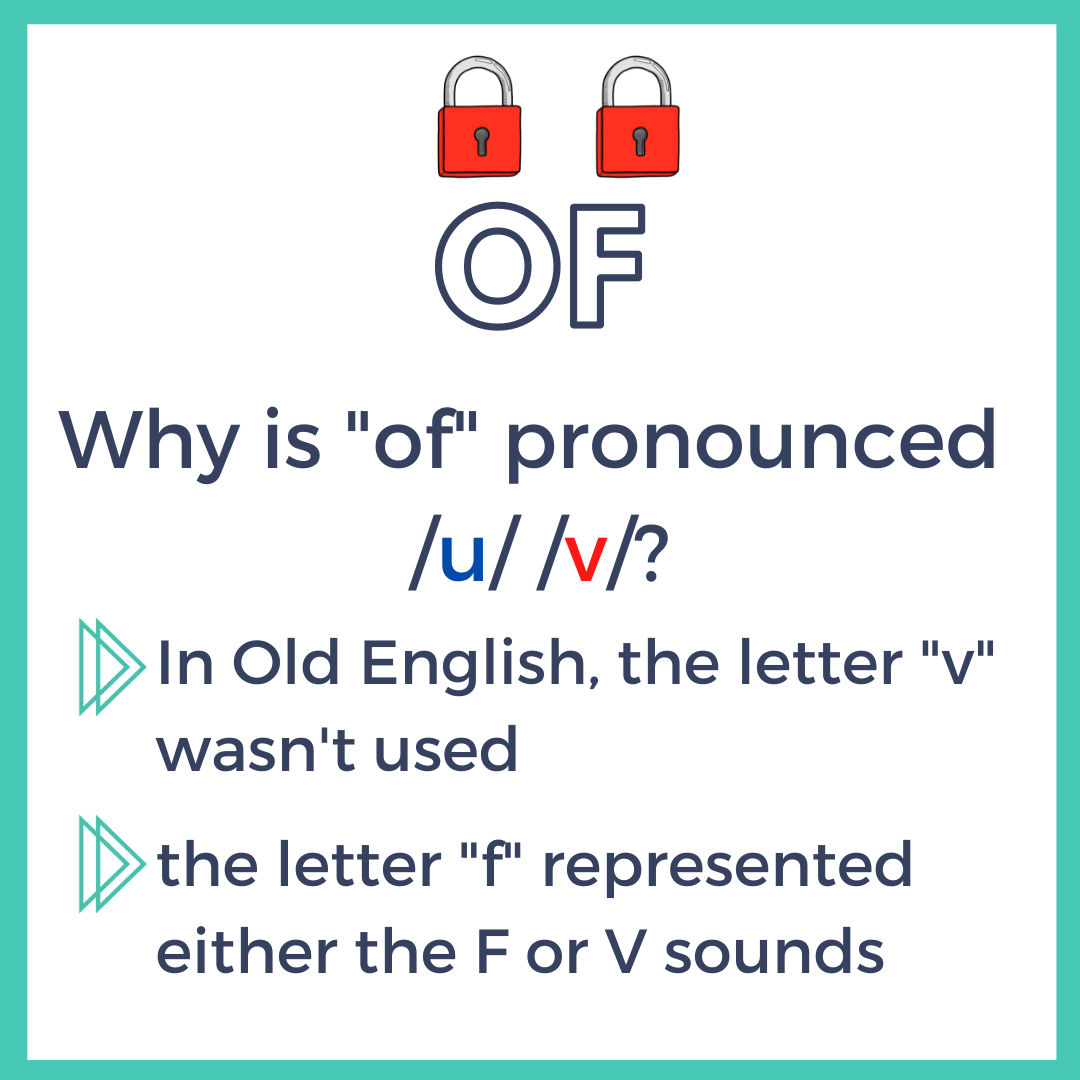

However, some words are not fully decodable. Words like “was” and “of” have at least one letter that doesn’t make a predicted sound pattern. These words that are not fully decodable are sometimes known as “heart words” or “red words” because at least part of the word needs to be memorized in order to sound it out effectively.

Notice I mentioned PART of the word needs to be memorized. The great news here is that usually, the entire word doesn’t need to be memorized.

So how exactly do we teach these words?

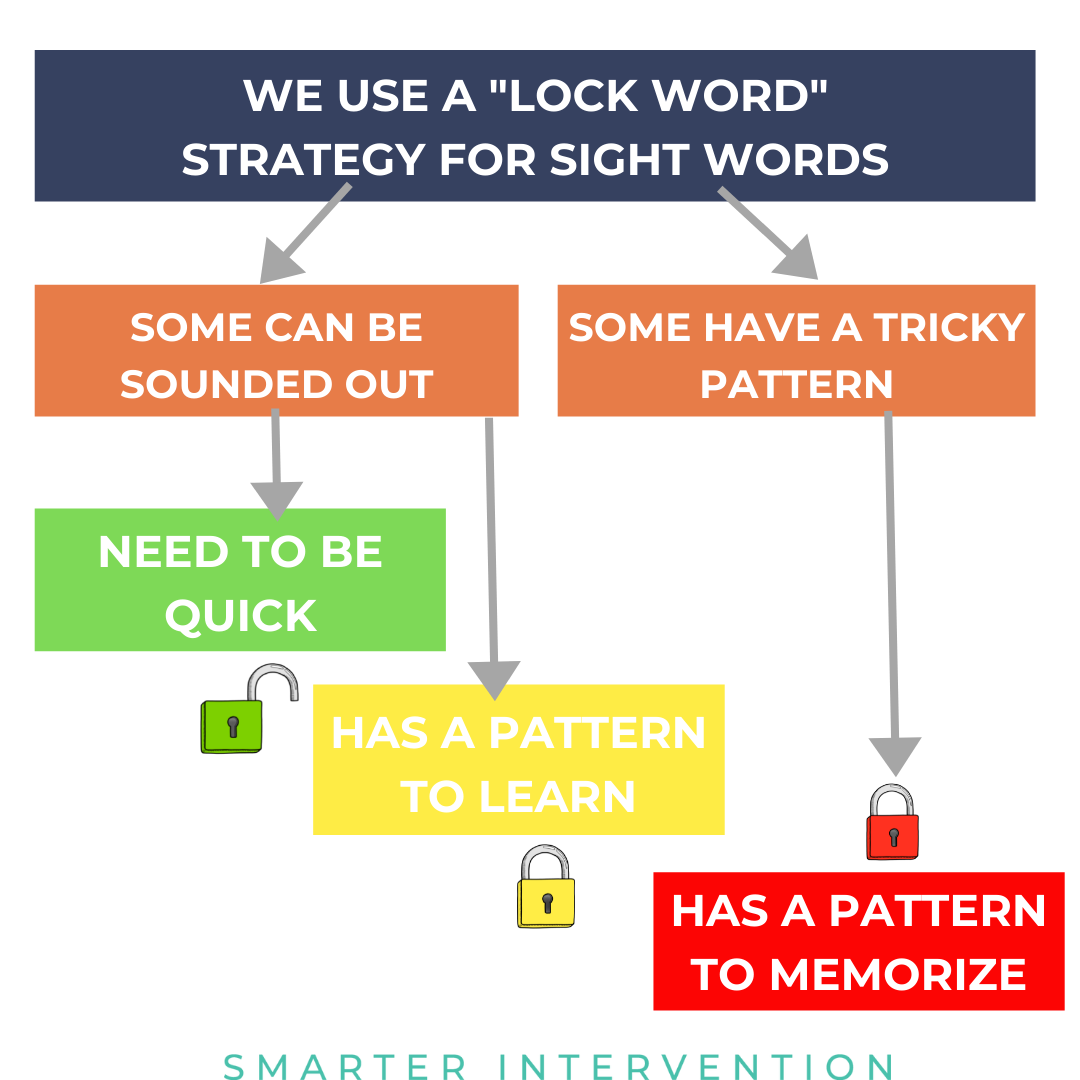

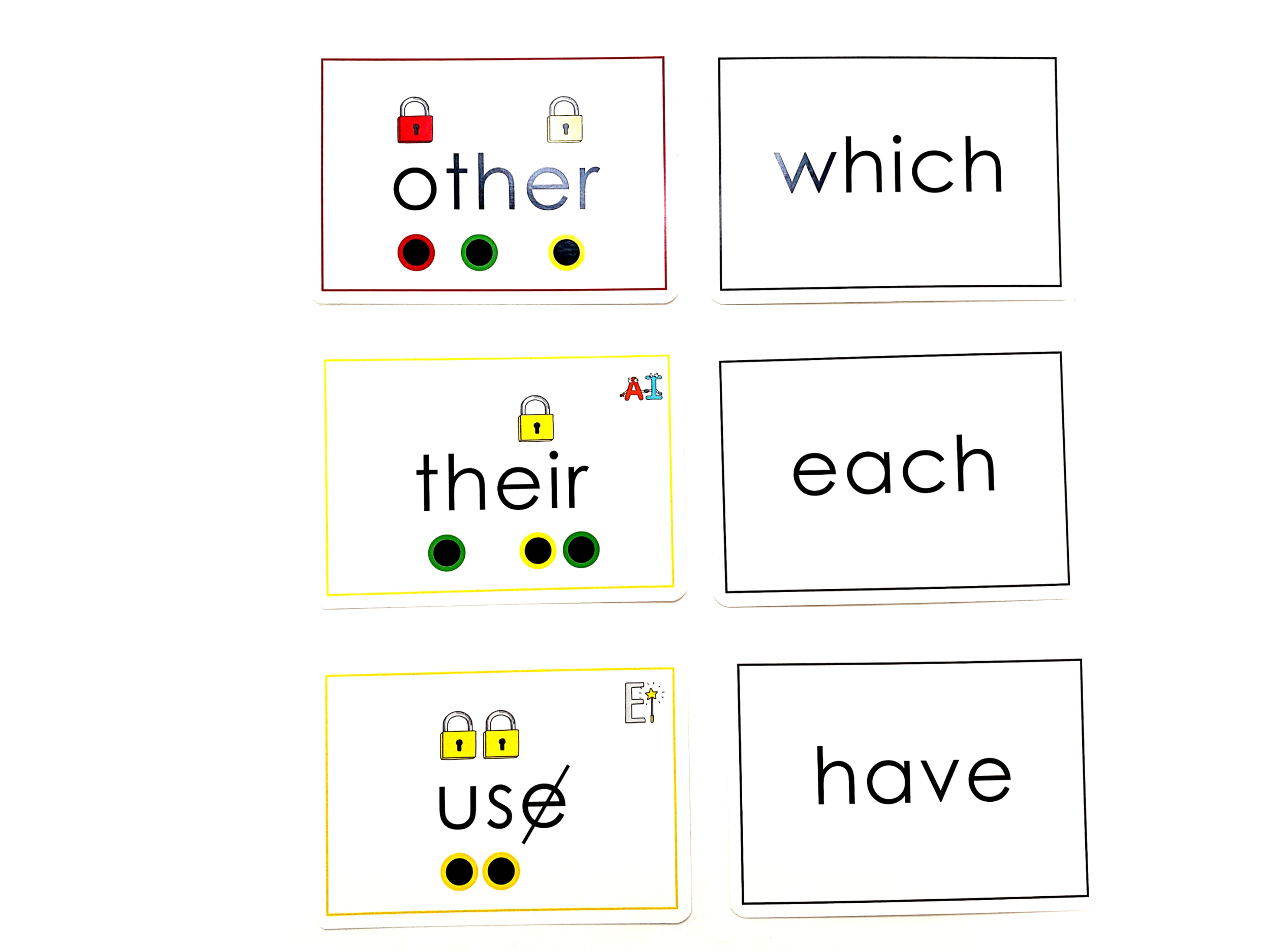

We use a “Lock Word Strategy” to teach high-frequency words (words that should become sight words). Essentially, these words need to be “locked” into our memory so that we can identify them by sight instead of needing to rely on a phonetic decoding strategy.

In order to help students retain or hold onto sight words, we break them into three different LOCK categories.

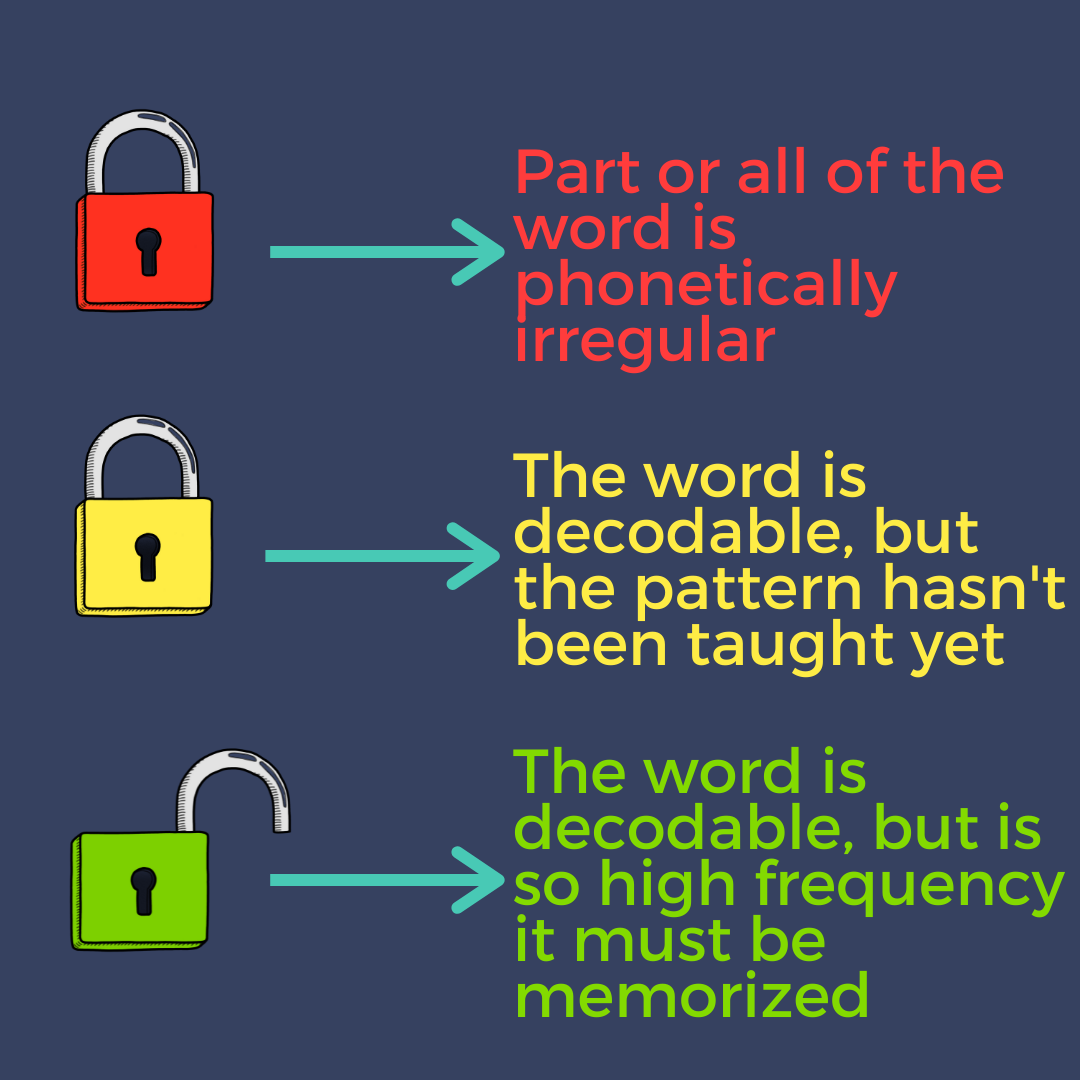

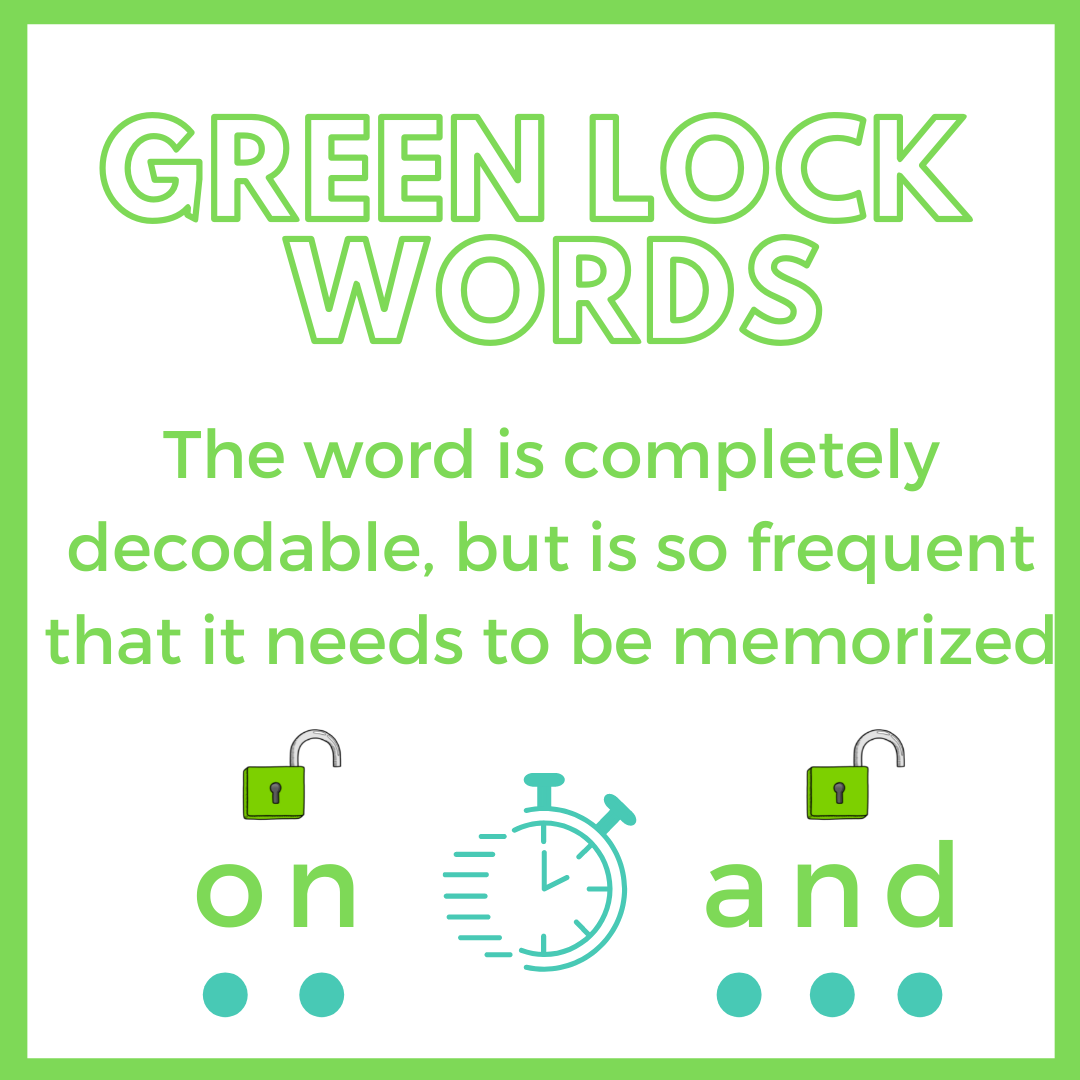

1 - Decodable words = Green Lock Words. These words are decodable which means they can be entirely sounded out with a student’s current level of knowledge about how to decode/sound out words. However, these words are high-frequency meaning they occur a lot so we want to “lock” them into our brains so that we can read them quickly, without having to labor over decoding them. We’re looking to build automaticity and reduce the cognitive demand required of sounding these words out.

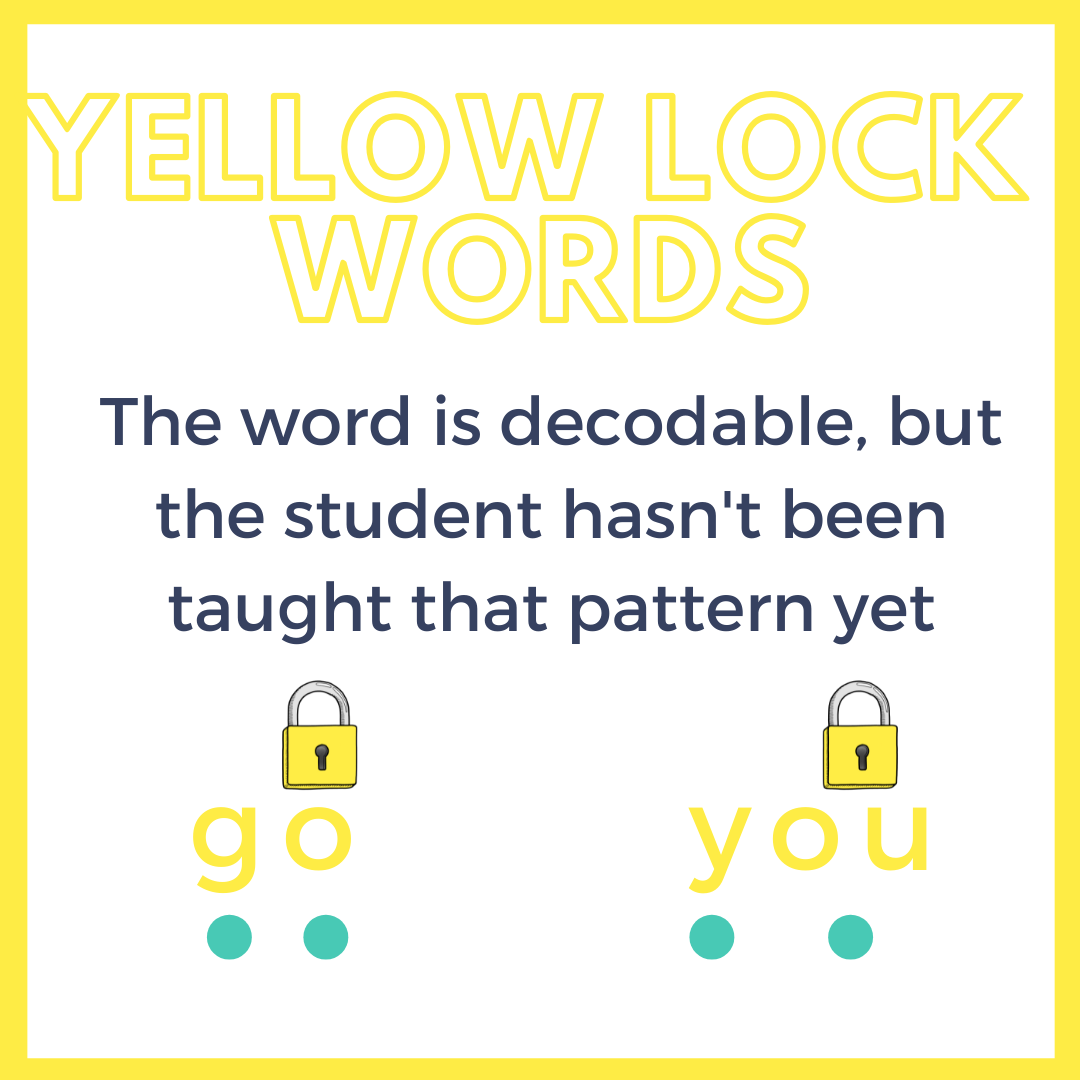

2 - Phonetically Regular (Will be Decodable) = Yellow Lock Words. These words are phonetically regular and could be sounded out, but not all of the patterns have been explicitly taught to the student. These often appear in high-frequency words. Again, they need to be “locked” into our memory since the patterns aren’t yet familiar AND we see them often.

For example, in the word “go” students may not have learned about open syllables which means they may not know that O makes the long sound at the end of an open syllable, or in the word “you” they may not have learned that “ou” says /oo/. Therefore, once the student learns about open syllables and the vowel team “ou” the word could be sounded out effectively - but students need to be able to read these words before they may have reached this level of systematic exposure we talk about here.

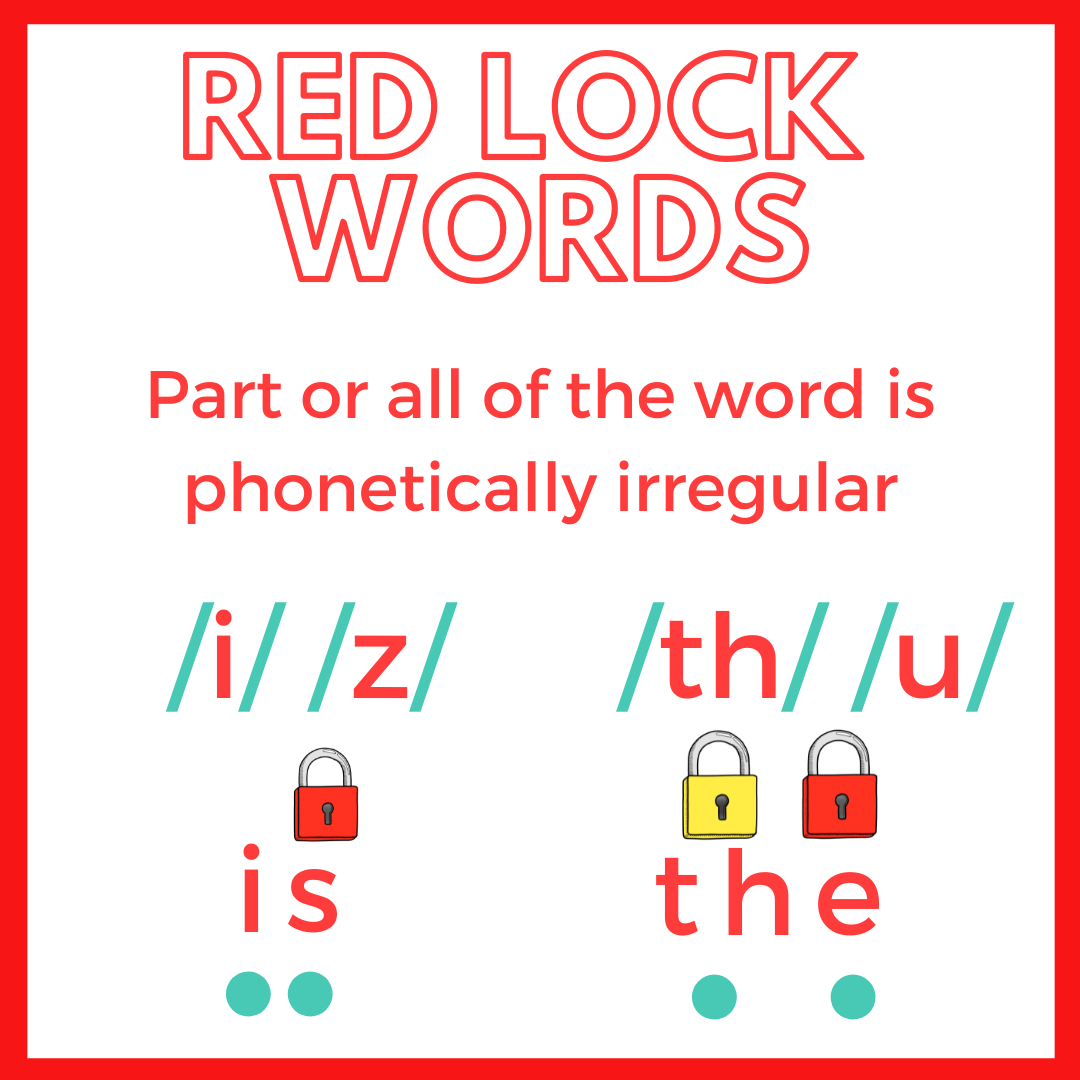

3 - Phonetically Irregular Words = Red Lock Words. These words are tricky because they have at least one pattern that can’t be sounded out. We have to “lock” these patterns in our memory because they don’t follow our typical rules.

For example, in the word “is” students need to recognize that S says /z/ which is unexpected because normally S says /s/ unless it is stuck between two vowels. We definitely want our young students to memorize this rule for the word “as” as well so we don’t have an uncomfortable moment in the classroom! (We’ve all been there!).

For the word the, we have a Red Lock Word because the e says /u/, and depending on the scope and sequence - if students hadn’t yet learned the /th/ pattern - we would want to make sure to explain to our students that TH comes together to say /th/ in this word, which is why the letters “th” only have one dot under them.

By breaking our words down into these three categories, we are able to help students “decode” these high-frequency words effectively until they’ve been transitioned into memory. This helps them bucket these skills and see the bigger picture, instead of trying to just memorize hundreds of words.

2 - Multisensory Instruction

SIght word instruction should be multisensory

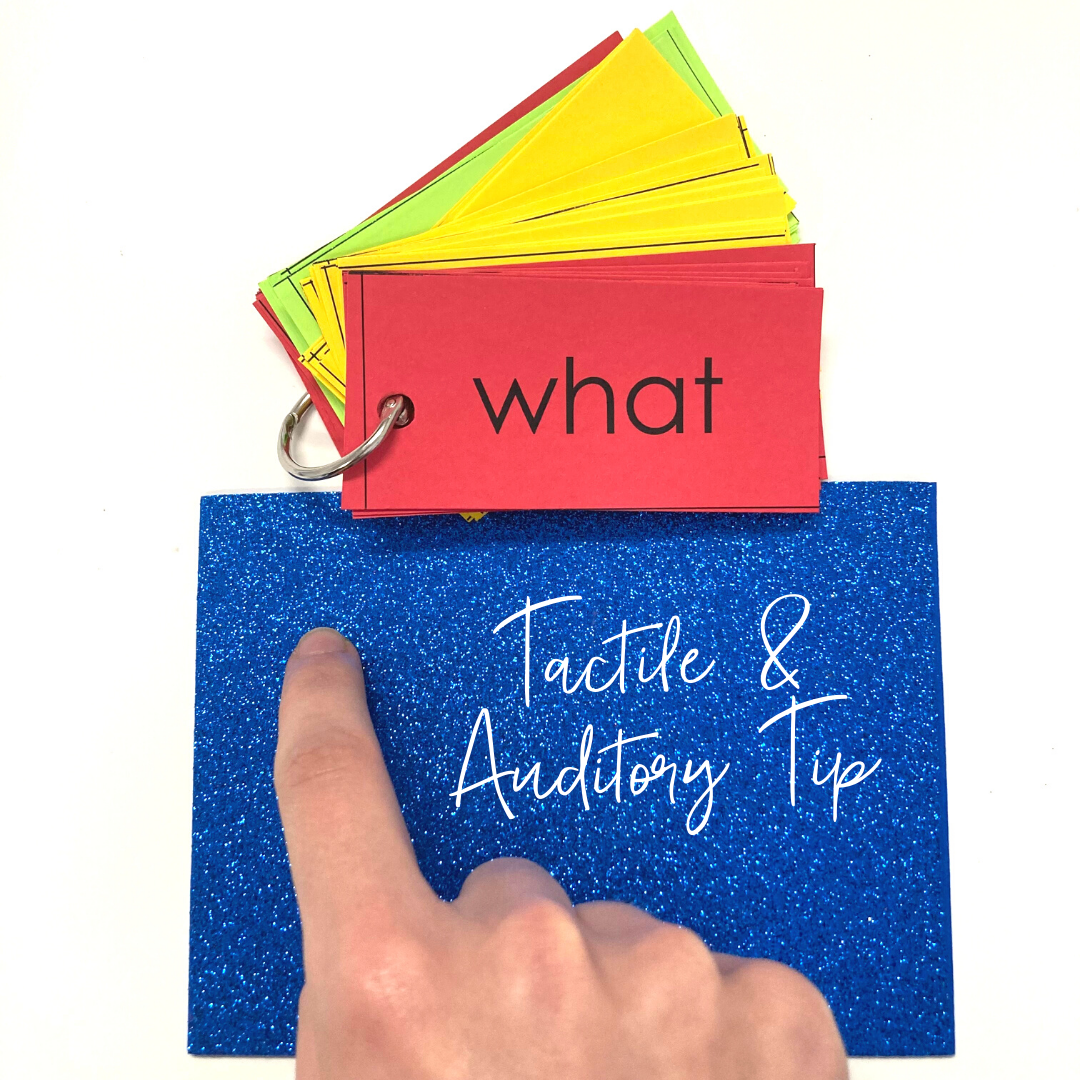

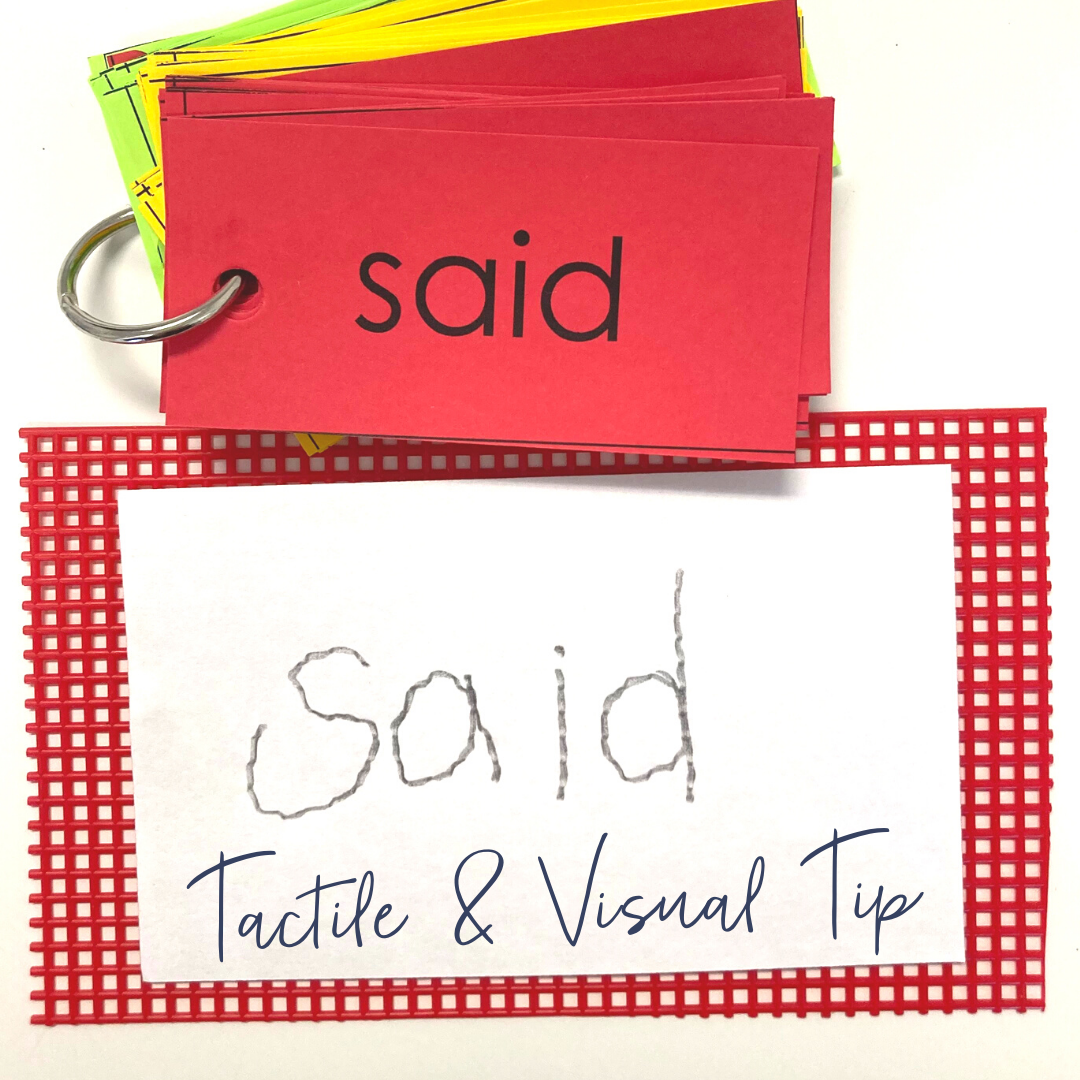

The first way we accomplish this is by providing the color-coding and lock symbol which immediately ties in an additional visual to help students with retention. Additionally, we want to think about ways we can add in auditory, tactile, and kinesthetic strategies wherever possible.

When practicing sight words we want to have students practice saying the letter name and not the letter sound since many patterns are irregular. For example, when practicing the word “what” a student would say W - H - A - T says what. Using foam glitter paper is an awesome way to practice! Additionally, having students practice writing over a tactile surface like a grid and then using their finger to practice tracing the word is another way to get in some extra tactile practice.

3 - Applied Instruction

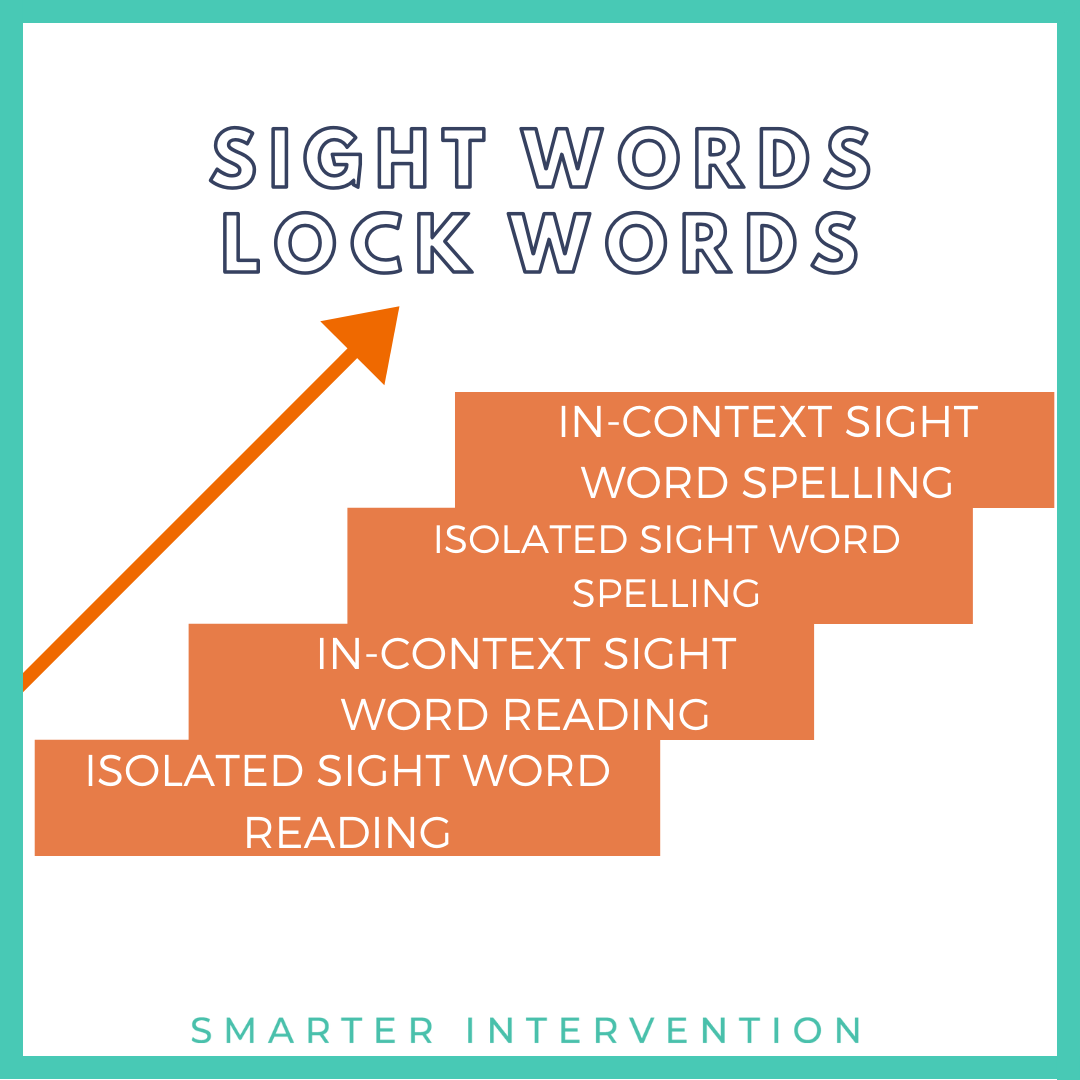

Sight word instruction should be progressive!

Reading and spelling lock words in isolation is definitely the first step, however, if we want our students to become fluent readers and writers we NEED to help them apply their knowledge when reading and in their writing!

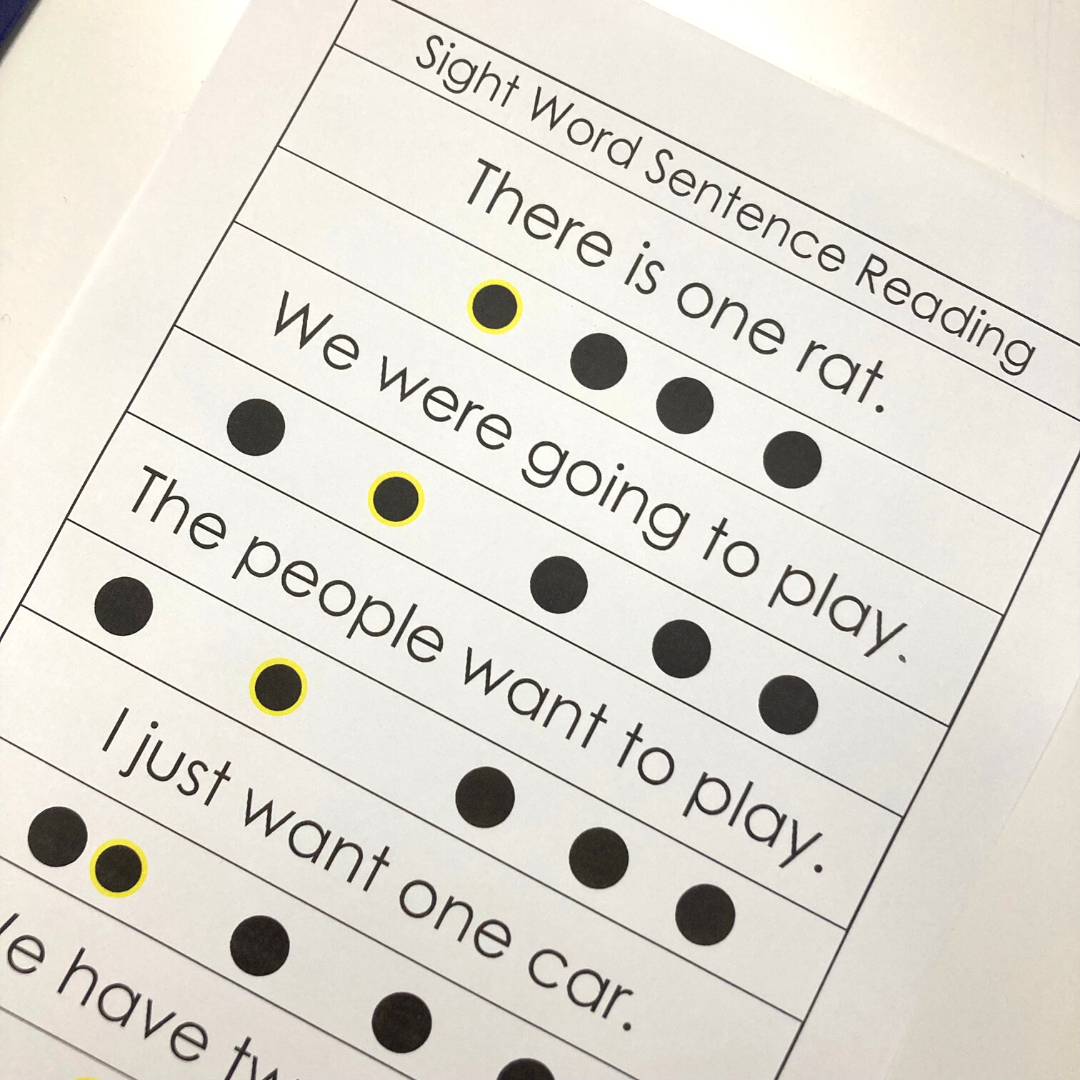

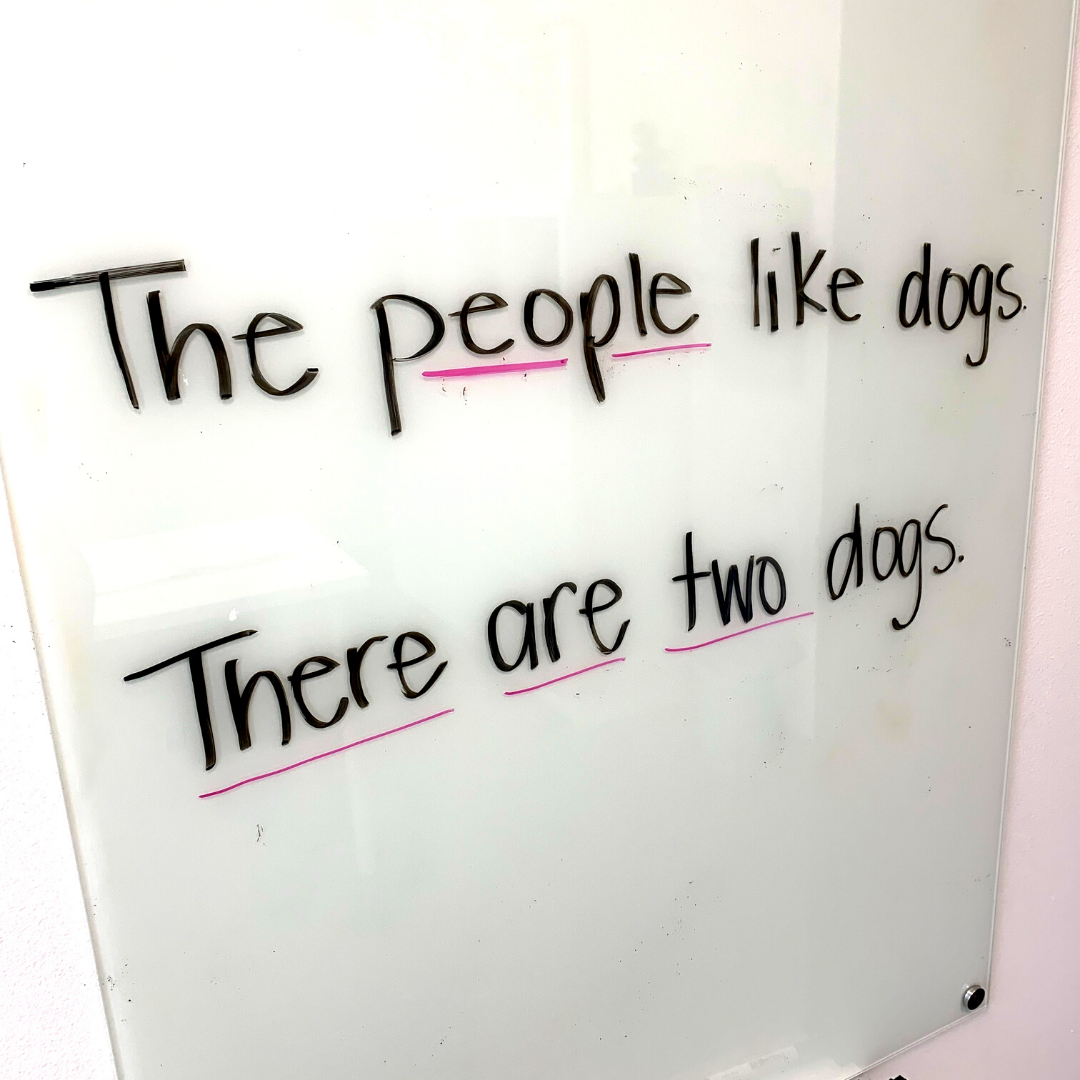

You want to start by helping students identify (read) words on their own efficiently. Typically to be considered a mastered sight word, students need to be able to identify what the word says in about one second. But reading sight words in isolation (all by themselves) isn’t enough. Once they can read the word you want to make sure they’re reading the word appropriately in context or in connected text.

Just practicing sight word flashcards doesn’t mean students are applying that knowledge to their sentence-level reading so it’s critical we help them make that jump.

You want to start by having students recognize and read the word automatically, you then want them to be able to recognize and read the word in the context of a sentence without sounding it out. The spelling of these words typically takes significantly longer, and that’s okay - just be aware the development of sight word automaticity in reading will happen much earlier than a student’s ability to spell the word.

4 - Research Behind Sight Word Instruction

Much of the research that had been done regarding sight word instruction using pure memorization techniques is surprisingly dated.

Many of us in the field of education have heard about Dolch words or Fry words, which are lists of words that are taught to students in primary levels. Dolch words were created in the 1930s by Edward Dolch, a professor and children’s book writer who researched words and created a list of 220 of the most common words used in children’s books during that time.

Edward Fry expanded upon this list, adding hundreds more words to a “sight word list” or a list of words students should know by sight. That list was last updated in 1980. Dolch’s words were specific to younger students in Kindergarten through 2nd grade, whereas Fry’s words were meant to be studied by older students in 3rd - 9th grade.

According to the National Institute of Child Health in the National Reading Panel Report conducted in 2000, the recommended approach is combining explicit phonics instruction with either the Dolch or Fry list of sight words. This combination helps students build fluency quickly by providing a base of words they recognize on sight along with a method for decoding unfamiliar words.

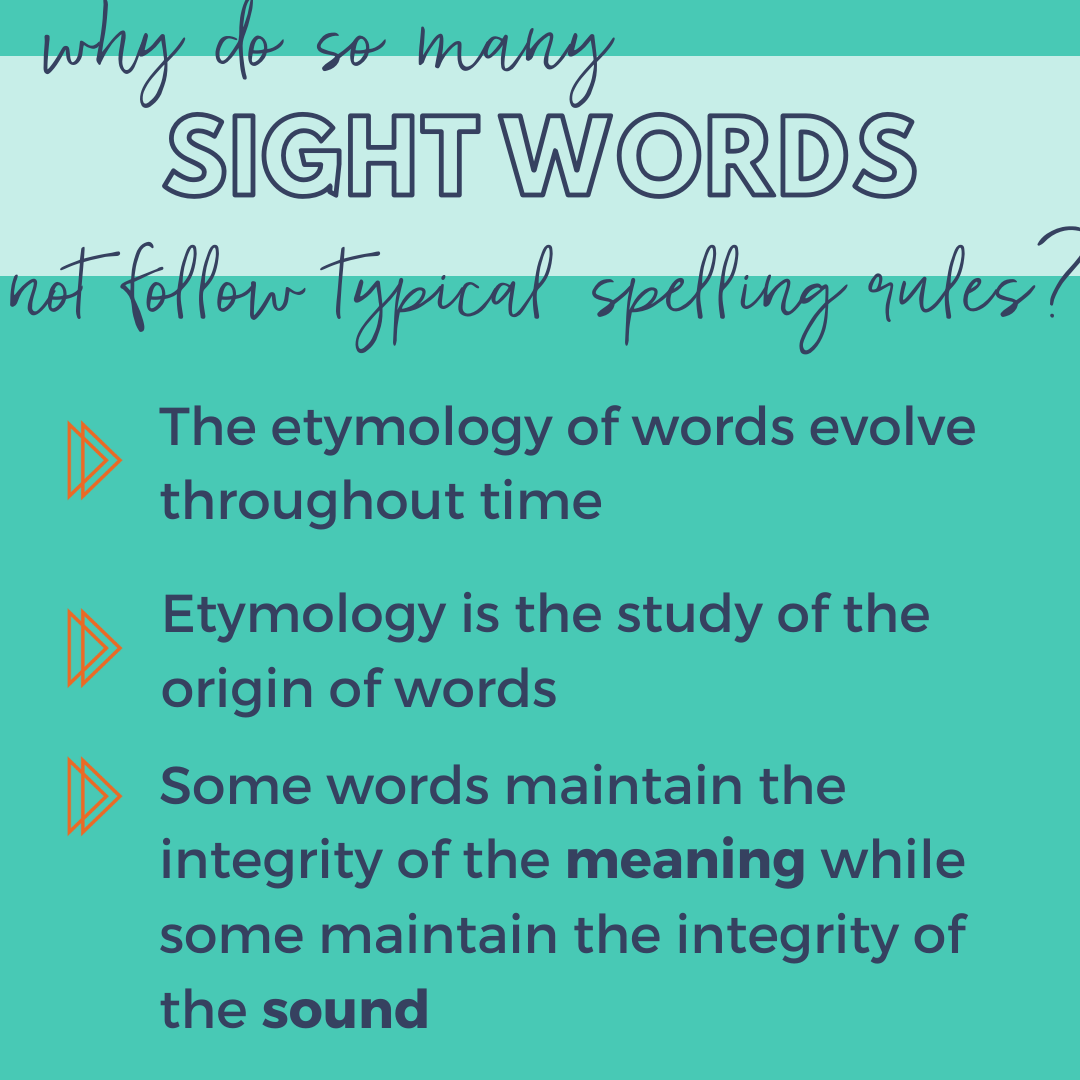

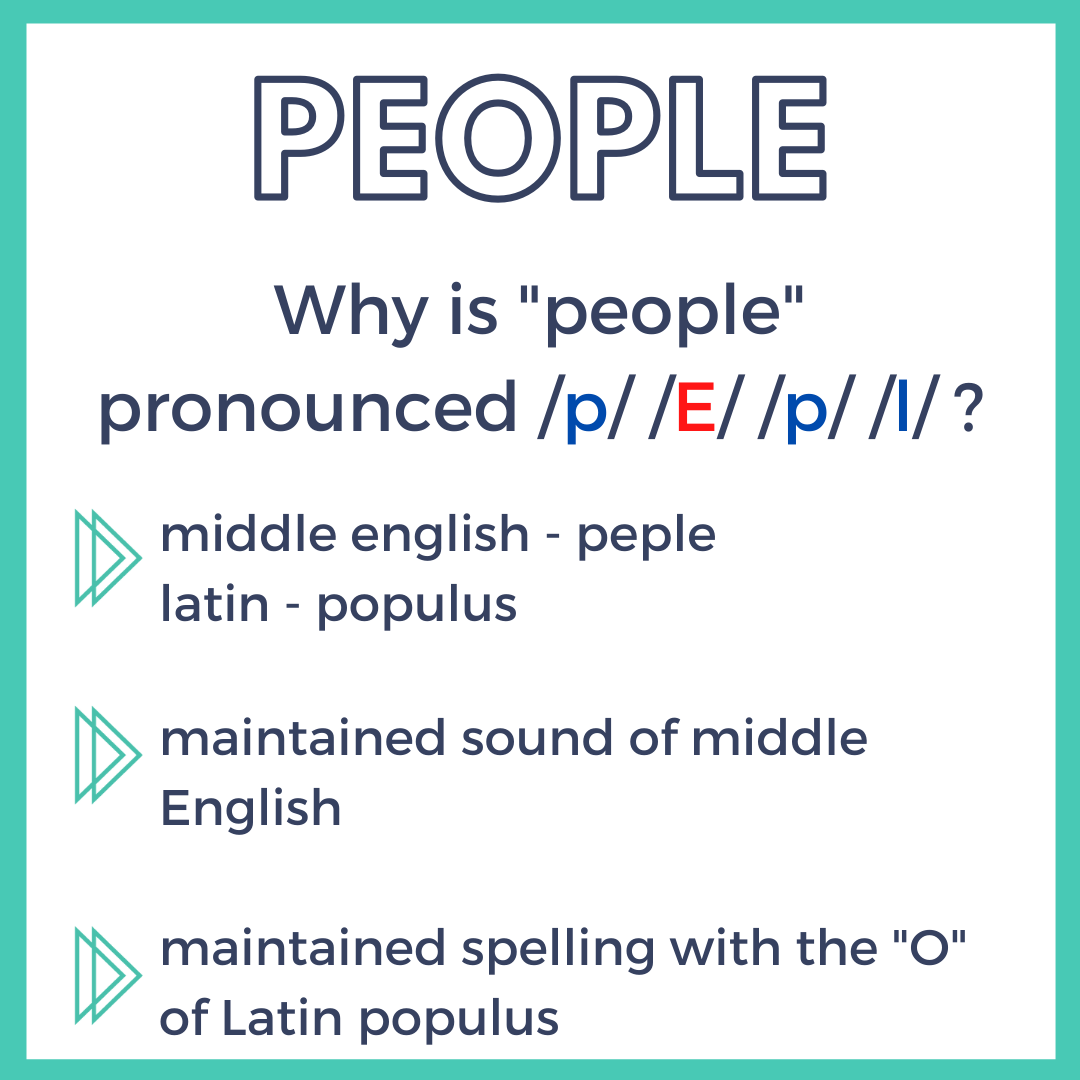

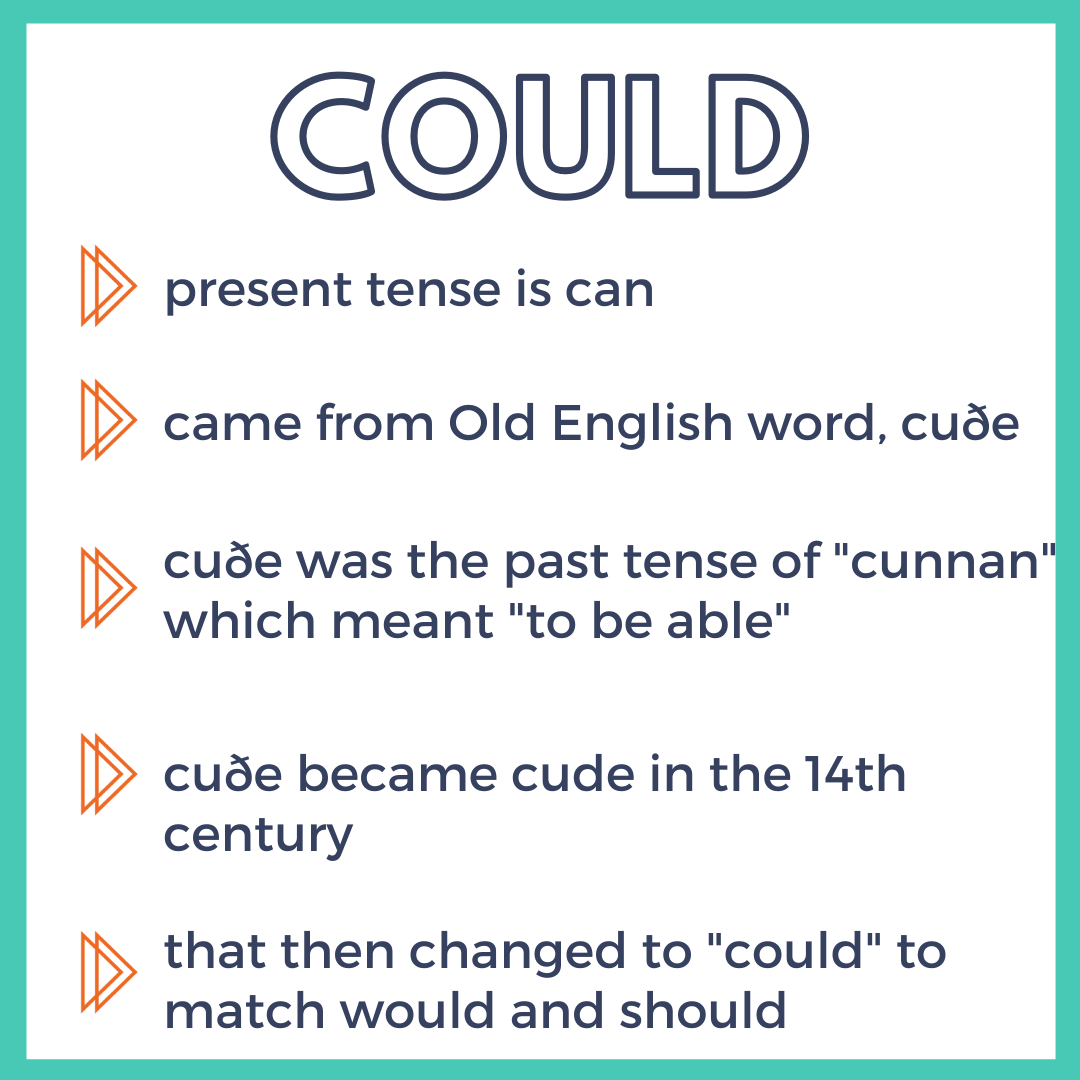

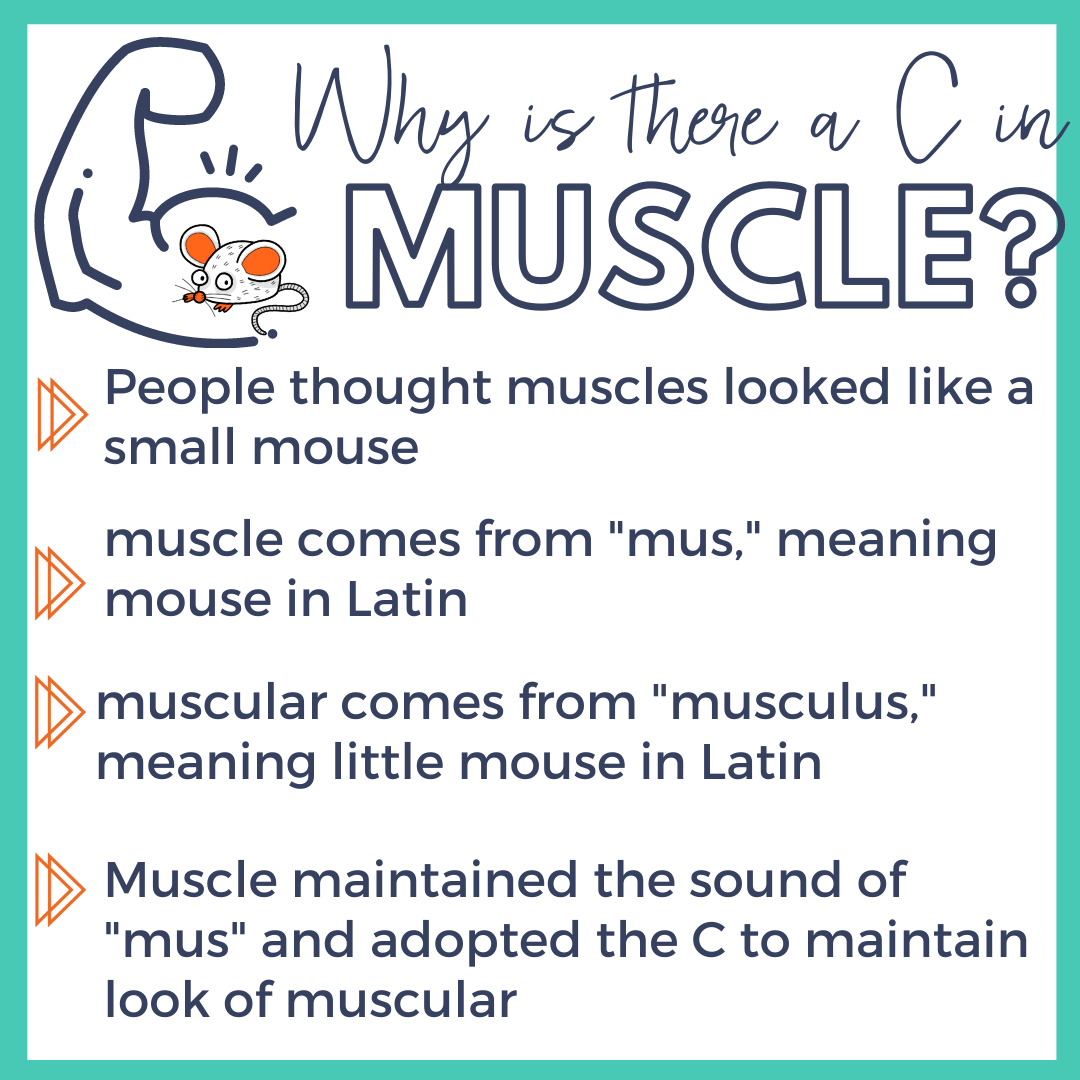

Now, the challenge with many of these words is that they are phonetically irregular or have parts of the word that cannot be sounded out and need to be memorized. We can help support this process by providing visuals or explaining the etymology (origin of the word and meaning) and morphology (parts of a word carrying meaning).

According to a study completed by Devonshire, Morris, & Fluck, (2013) adding instruction in morphology and etymology increased student retention of words above and beyond traditional phonics. This is especially important when traditional phonics patterns don’t apply.

5 - Targeted Instruction

Your instruction should target the words that your students need to know!

When teaching high-frequency words, we want to make sure the words we are teaching are actually important in instruction.

By putting together word lists based on frequency and common words at different grade levels you can then determine which words students need to know.

Ideally, students who aren’t struggling readers should be provided screeners to make sure they’re recognizing these common words by sight.

If you’re working in smaller groups or 1:1 you can use similar screeners to see which words to focus on with your students.

We also want to think about how many new “lock” words a student can learn at a time. Some students can read up to 5 per week, others do better with only 1-2 new words per week. If you have students who are struggling to learn these words, we recommend starting with the phonetically regular, high-frequency words (green lock words) first.

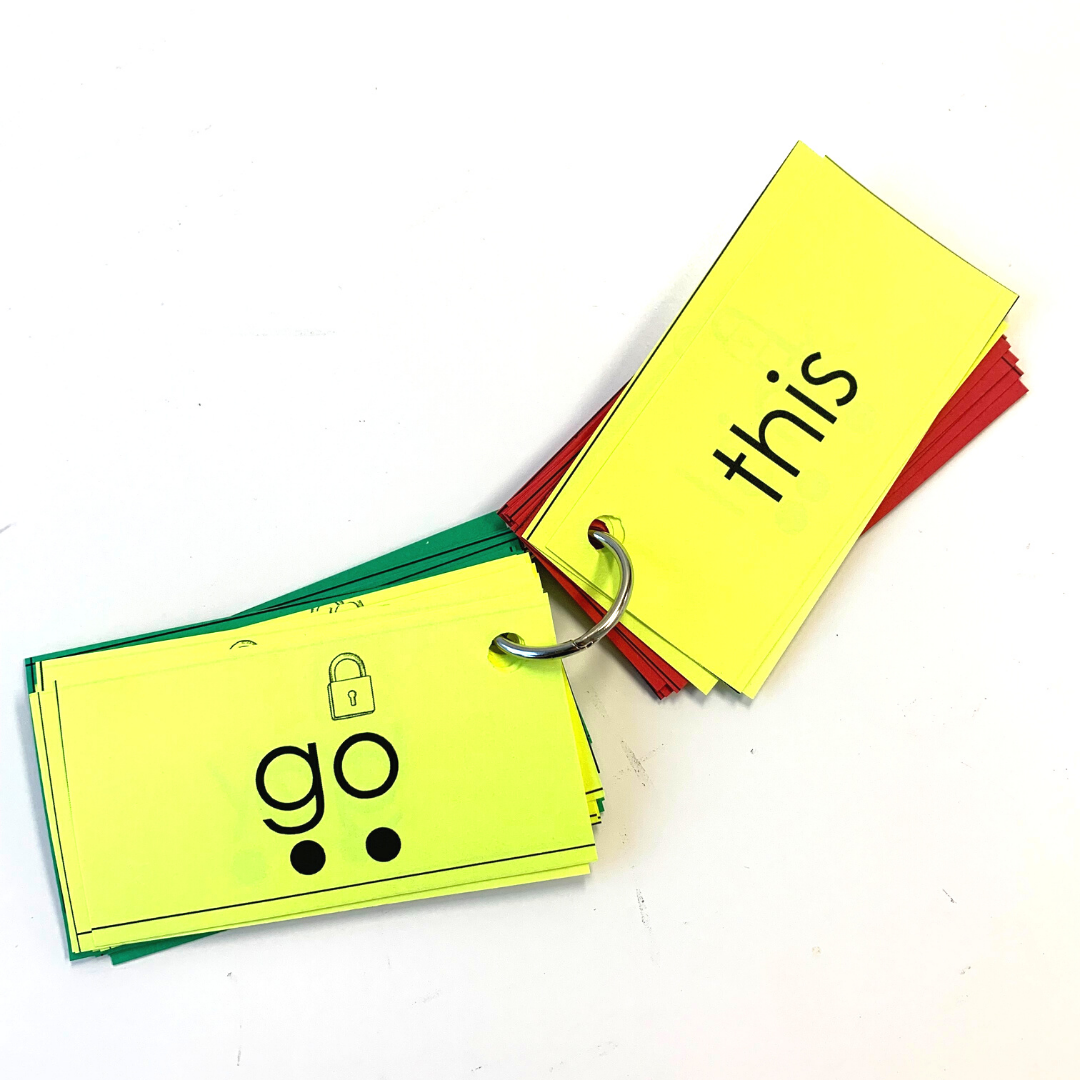

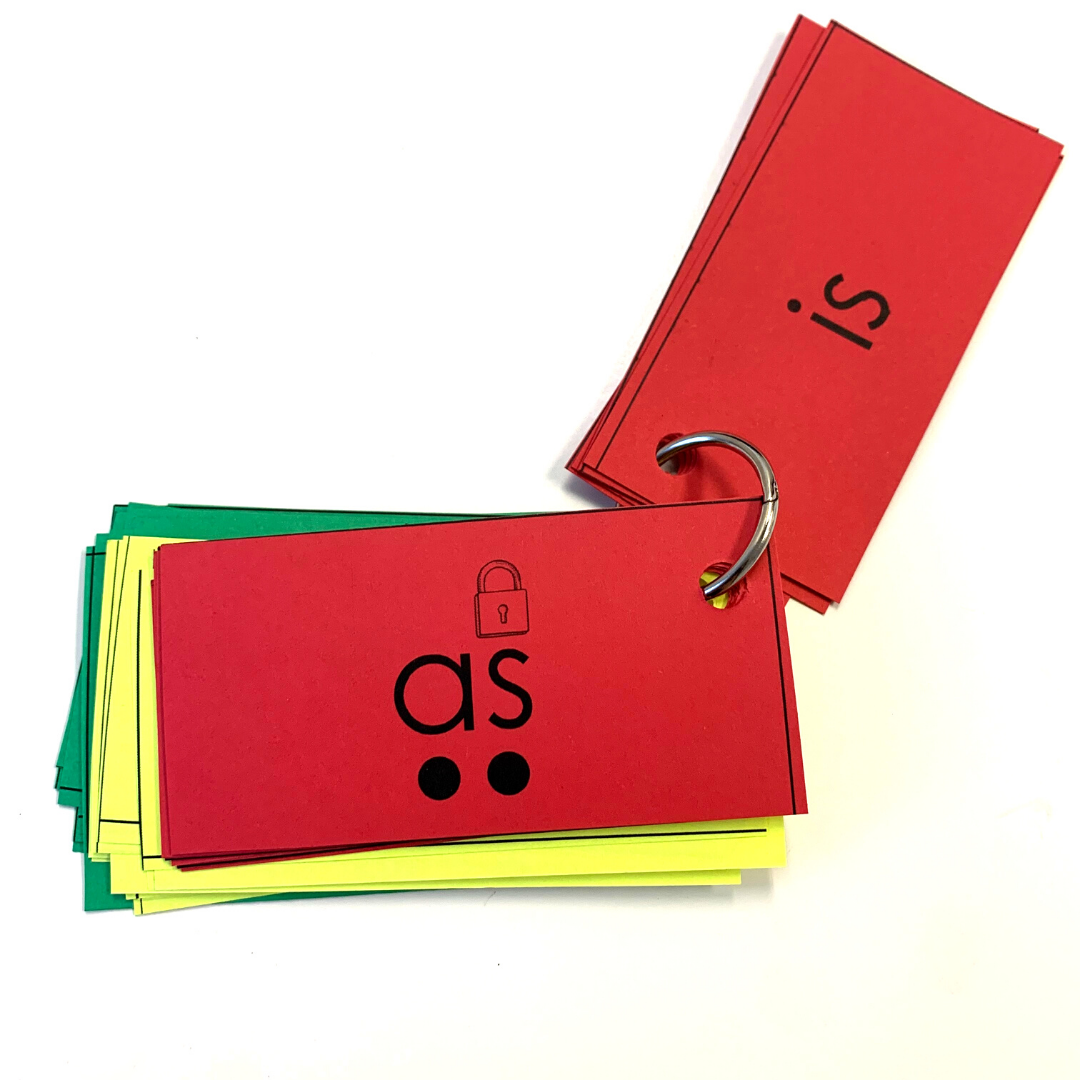

You can grab our sight word/high-frequency words card deck here!

6 - Explicit Instruction

The biggest hallmark of research-based instruction is that the instruction must be taught explicitly, meaning that we don’t assume students have prior knowledge of foundational reading and spelling concepts just because of their age or reading/spelling ability.

We should be using explicit phonics instruction to teach these words wherever possible. When explicit phonics instruction doesn’t work, we want to give students as much information and practice as possible to be successful with these high-frequency words.

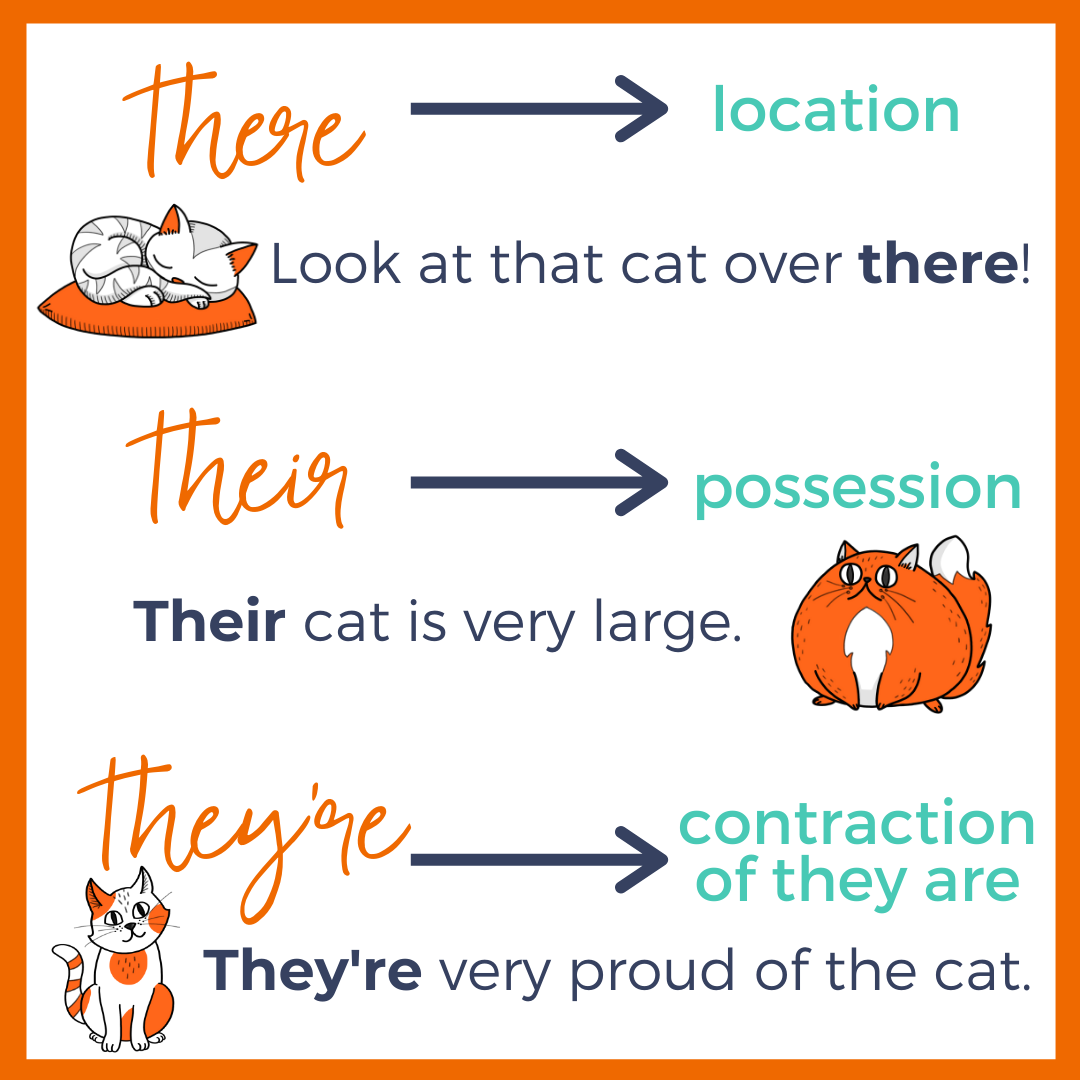

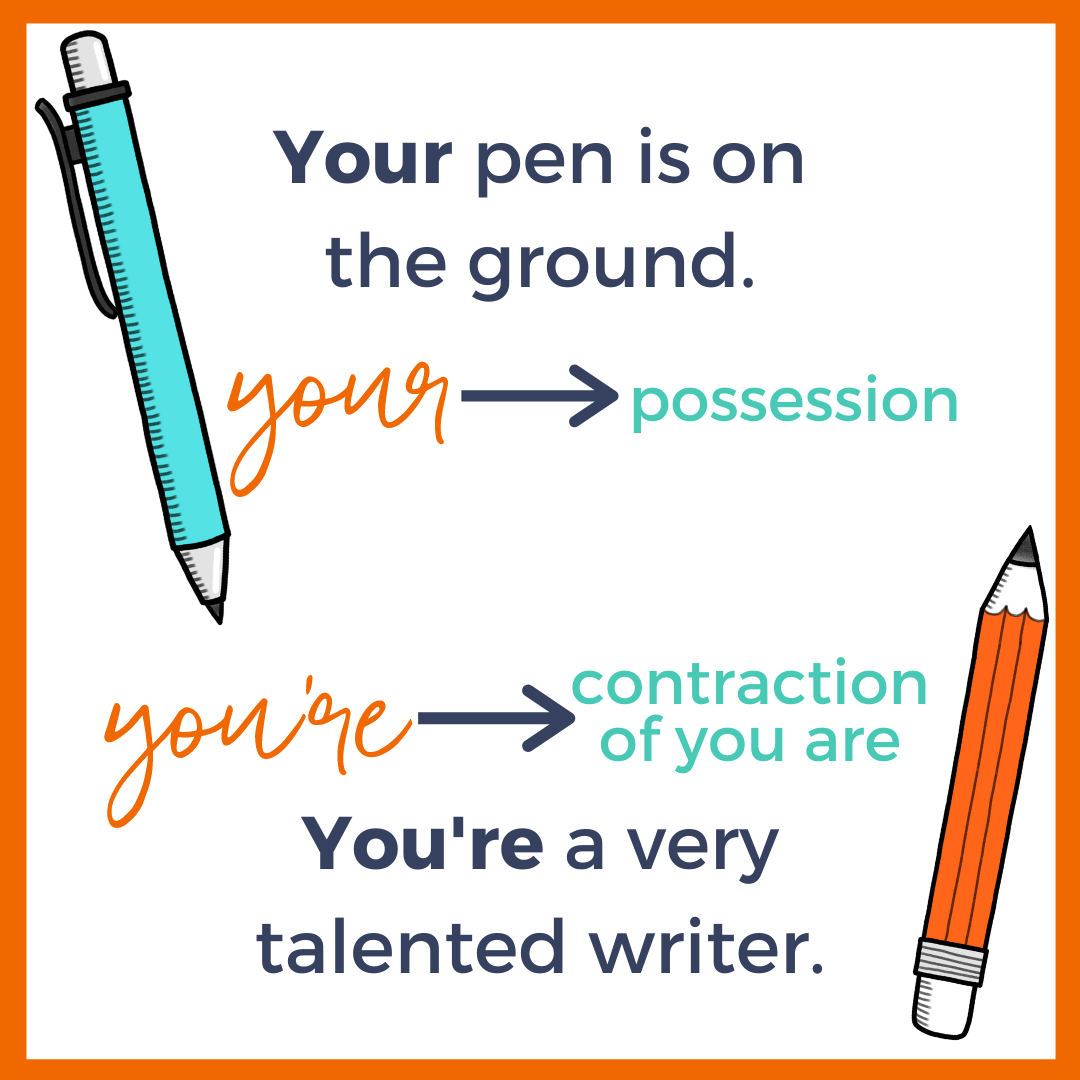

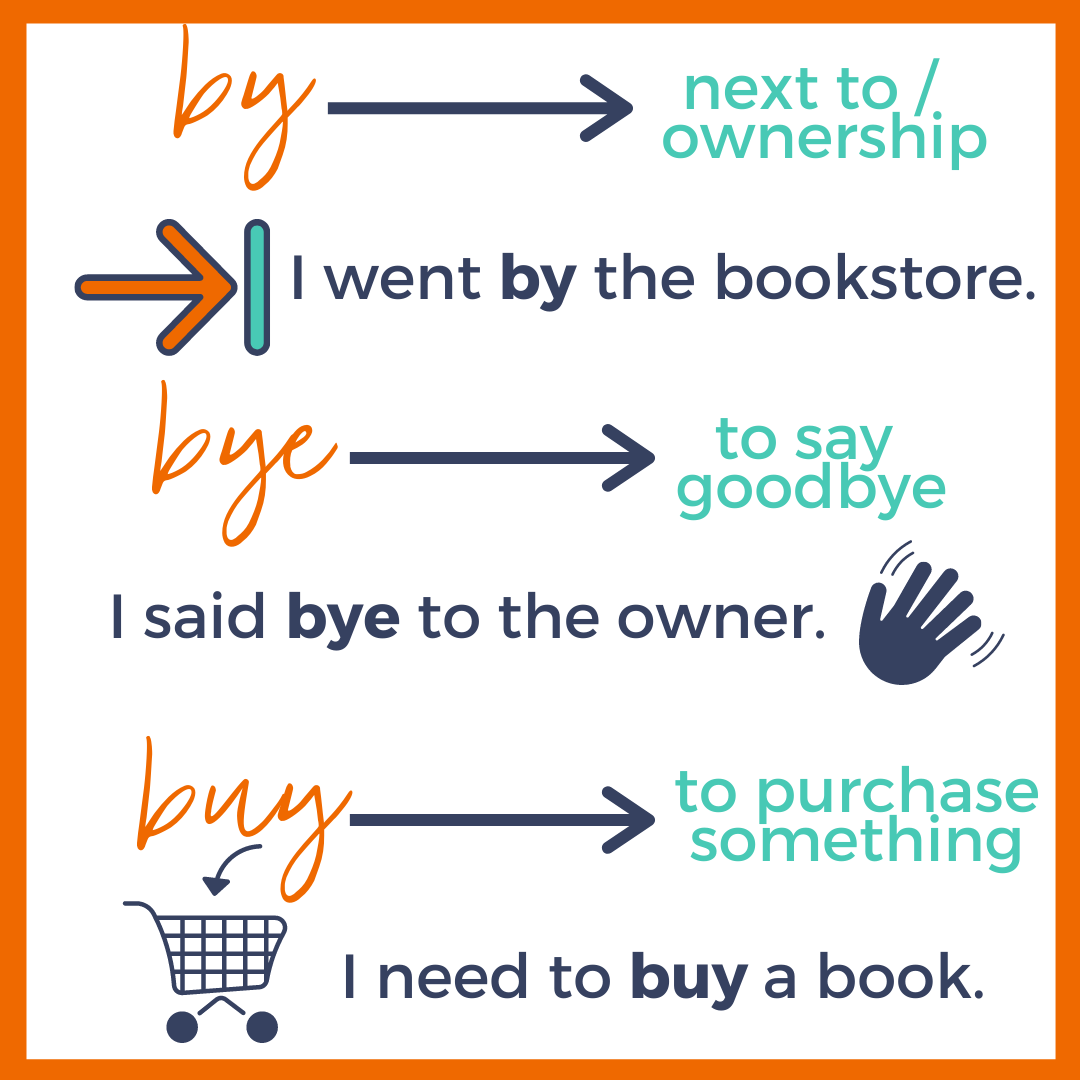

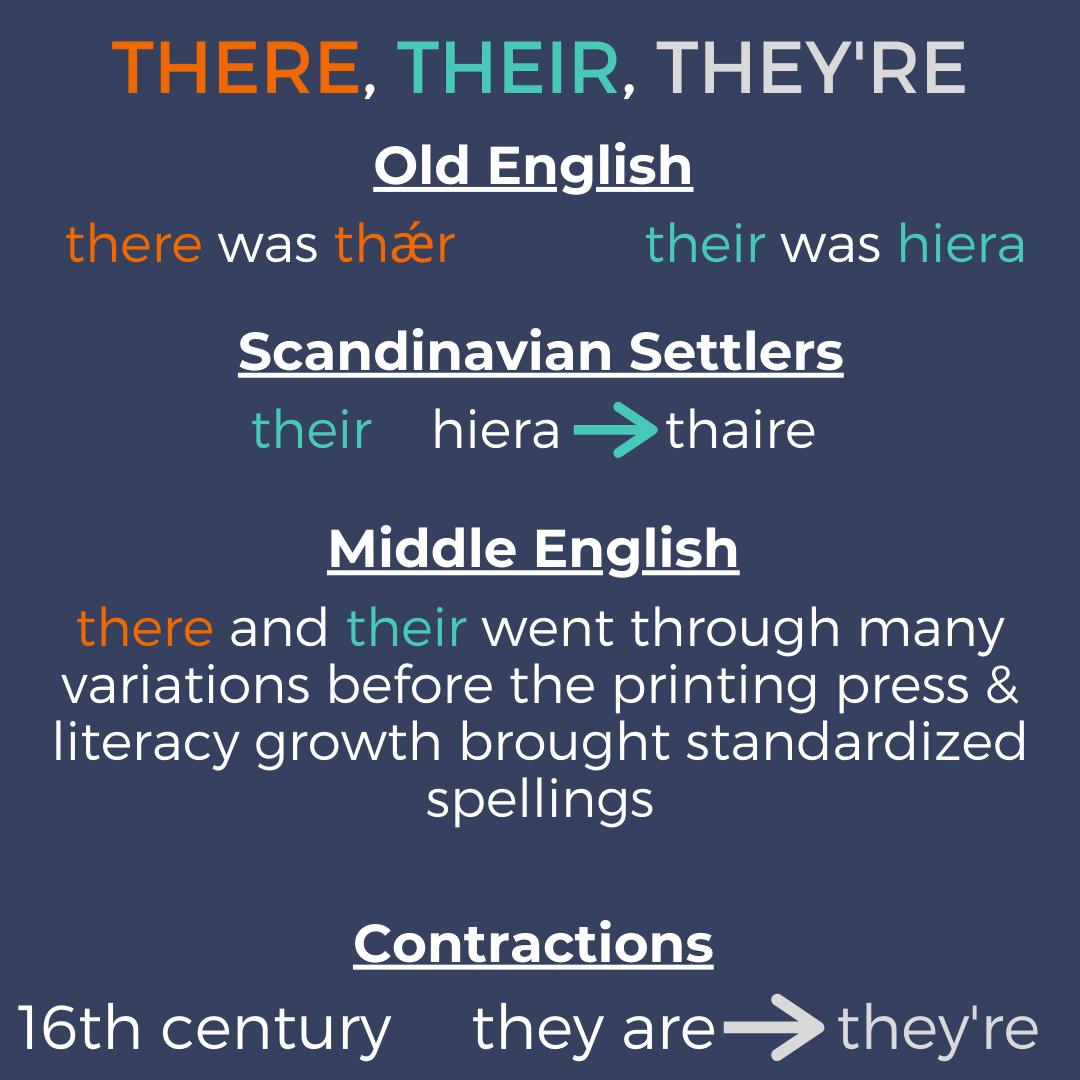

One helpful strategy is combining words or grouping words into categories such as homophones.

Homophones

Visual cues like the examples below are a great support to help students solidify their understanding of these words. Again, many of these patterns are phonetically irregular and need to be memorized as a “red lock word.”

We can also explain complex words in terms of etymology.

We don’t always dig this far into the weeds but for students who can access a higher-level explanation, you can also teach them about the etymology of the words and why they are spelled the way that they are.

Etymology

Explicit sight Word Skills to Support Reading & Spelling

As you work through your lock word (or any variation of lock words, sight words, red words, or heart words) instruction, we suggest starting by explicitly teaching students how to approach the word. Teach them what sounds are phonetically regular and familiar, phonetically regular but still unfamiliar to them, and phonetically irregular. Then, move on to homophones.

As for the etymology - we need to be realistic here (which brings us to our seventh and final step).

7 - Realistic Instruction

Is etymology really that important?

When it comes to our lock words - etymology can be helpful in understanding why certain words “break the rules.” However, we need to be realistic about the amount of information our students can access and how much they actually need to be functional readers and writers.

It will always be more important that students can read and spell the word muscle, than knowing that it comes from a Latin term meaning “little mouse.” If etymology feels out of reach for your students - then don’t worry about it. If it doesn’t contribute to them having a functional ability to read and spell, it isn’t going to be worth your time or their time in the long run.

In addition to being realistic with our students, you also need to be realistic with yourself.

Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.

Now obviously there is A LOT that goes into research-based instruction, including lock words, but again, it does not have to be difficult. One of the best things you can do is to start thinking about where you can incorporate these activities into what you’re already doing. The best instruction is the instruction you can actually deliver and keep up with, without burning yourself out!!!

If you want to grab a comprehensive set of lock words that we use with our students you can check out the High-Frequency Word Deck using the button below!